Two marathons of spin, 77 years apart

The two Durbanites with a penchant for bowling marathon spells

Thank you for reading 438 & Beyond. If you like what you read, please click the button below, join the mailing list for FREE and share, on social media or through e-mail or however you feel comfortable sharing.

To support this project and keep things going, please consider becoming a Patron or buying a coffee.

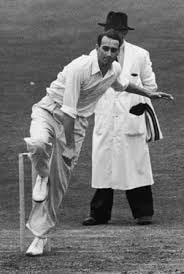

Everyone around him called Toey. Some bowlers do a shuffle, others walk around their mark before getting into stride... there is no end to the little things bowlers do at the top of their mark. Hugh Tayfield stubbed his toe into the ground before he got into his delivery stride. Tayfield didn't always do this. He didn't stub his toe when he was a youngster.

In his youth, he bowled tame, ineffectual, back-of-the-hand deliveries. It was a combination of his batting and fielding that got him into the Durban High School XI side. Tayfield transformed as a bowler after his school captain, a leg-break bowler, suggested that he try bowling off-breaks. Tayfield took to it like a duck to water. In his first match as an offie, he snared three wickets and that was enough to convince him to take the trade seriously.

It is also doubtful that Tayfield stubbed his toe at this point of his career, there is no way it could have gone unnoticed for so long. The Australians were the first to notice it during the 1949/50 season. The funny thing is that the toe-stubbing was not Tayfield’s defining oddity. Opposition players and spectators knew him for something less ‘eccentric’. In 1953, Tayfield found himself at his wits’ end against Australia. He couldn’t buy a wicket.

Tayfield was the king of funky field settings. He liked to have two short mid-on fielders, standing as close to each other as possible, sometimes their shoulders touching. He also liked to add two short covers to this setup. All four lay in wait for the uppish push or drive. Tayfield also had a penchant for leaving the extra cover region open and floated deliveries, encouraging the mistimed drive.

Against the Australians, Tayfield asked his captain for the funkiest fields he could imagine, but that didn’t help. He asked his teammates for suggestions as to what he could do, but they had nothing useful. At one point he kissed his cap badge before handing his cap to the umpire at the start of the over. Tayfield dismissed Arthur Morris in the over, and from that day, Tayfield kissed his headgear before handing it to the umpire.

In February 1957, South Africa were trailing 2 - 0 in a five-match series. They had lost the first two and drawn the third in Durban. The hosts needed to win the fourth Test to stay live in the series. In their first innings, South Africa scored 340 on a batter-friendly pitch. England stumbled to 261, thanks to Peter May’s well-played 61 before the hosts made 142 in the third innings for a 231-run lead.

Clive van Ryneveld, the South African captain, threw the ball to Tayfield. The offie picked an end, stubbed his toe into the ground 280 times, kissed his cap 35 times as he delivered as many 8-ball overs, and laboured throughout the four hours and fifty minutes of the final day. The English bowlers heavily punished him early on, but he maintained his poise and bowled South Africa to victory.

That was South Africa’s first victory over England at home in 26 years, and the first time a South African bowler bagged 13 wickets in a Test.

South Africa has used 32 spinners in Test cricket since Tayfield’s retirement and only one has come close to both his figures and ability to influence the course of a match.

Normally, I ask you to support the newsletter, but at the moment, I have a bigger ask, if you can spare a little bit, please contribute to my son’s cancer treatment and recovery. Many people have been generous, but we have not yet reached the full amount required. You can also help by sharing the link:

Shukri Conrad wheeled out a line-up with the balance of a three-legged table to face the West Indies in the first Test. Wiaan Mulder, who has a higher ceiling as a batting allrounder and a good fourth or fifth bowler, was asked to be the Proteas’ third pacer. Conrad’s attack had two frontline pacers, Kagiso Rabada and Lungi Ngidi, and Keshav Maharaj as the lone spinner.

The pitch had nothing in it for the bowlers. It was slow and kept low. Wickets were dependent more on batters’ errors and runs were laboured. It was a perfect recipe for a snooze-fest. In the run-up to the first Test, Kagiso Rabada spoke of the need for smaller nations to play entertaining cricket.

But that excitement did not come about until the 13th over, and the author of that drama and intrigue was Keshav Maharaj. The spinner was all filigree fingers and elegant elbows as he settled into an untiring and metronomic groove, not too dissimilar to one that his fellow Durbanite, Tayfield, had 77 years earlier.

Maharaj used his control and subtle variations of pace, trying different angles to coax something out of the pitch. The rain that washed out a lot of the first innings meant that when the ball went to the outfield it got wet and became soft. The Proteas did what they could to keep it as dry as possible.

He sent down his first delivery in the 13th over and his last of the first innings was the 91st of West Indies’ reply. It was his 40th. 28 of those overs were consecutive, uninterrupted from the Media Centre End. He bowled the next 12 the next day. Kagiso Rabada, Lungi Ngidi, Wiaan Mulder and Aiden Markram rotated at the other end through Maharaj’s 40-over marathon.

Maharaj snared the crucial wickets of Mikyle Louis, Keacy Carty, Alick Athanaze, and Jason Da Silva. Three of those wickets were top-four batters.

With a healthy lead, South Africa had an opportunity to extend it a little further, put it just beyond West Indies’ reach and push for a win. Maharaj took the new ball and gave the Proteas hope with a wicket in his first over. The spinner took four of the five wickets and bowled 26.2 of the 46.2 overs. The Proteas had hope because Maharaj was operating from one end.

It is the kind of thing Tayfield did for South Africa in the 50s. Not only did he bowl the most overs regularly, but he also put his side in winning positions. In this match, Maharaj bowled around 45% of South Africa’s overs in the match, which is higher than Tayfield’s 39% in the historic February 1957 match.

While there are numerous matches where he did not bowl or delivered less than 10 overs, Maharaj’s first innings marathon wasn’t his longest. He bagged five-wicket hauls in two of those instances. He has sent down more overs in nine of his previous 84 bowling innings and has delivered more than 66.5 overs in a match four times in his career.

It also wasn’t the first time he and another spinner had taken the new ball for South Africa, as Maharaj and Aiden Markram did after 80 overs. He has previously shared the brand new cherry with Simon Harmer at the start of the fourth innings against Bangladesh at Kingsmead in March 2022.

When he gets hold of the ball, it's difficult to take it away from him, and he often makes good use of it.

“When you bowl in the right channel for a long time, you get results,” Maharaj shared after the first innings. He finished the match with 8/164. Not his best bowling figures in a match, Maharaj has a career-best of 12/283 and an exceptional 9/129 in an innings.

Maharaj is the first spinner to come close to Tayfield’s haul of 170 Test wickets. As it stands, Maharaj, who has sent down 3595 fewer deliveries than Tayfield, is only four wickets behind the man considered by many as the best spinner from South Africa. He also looks set to be the spinner with the most wickets for the Proteas. A record that won’t be broken, with the direction cricket is taking.