Geoffrey insists that Tupac Shakur is the greatest rapper of all time.

This is his escape, uplifting and emotional hip hop tracks that include Dear Mama, Unconditional Love, Brenda’s Got A Baby, Ain’t Mad At U, Troublesome ‘96 and California Love.

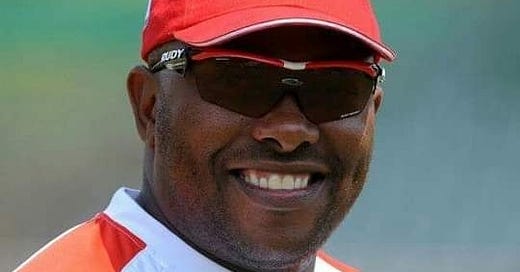

In 2012, Geoffrey Toyana became the first black African coach of a franchise in South African cricket, with Lions.

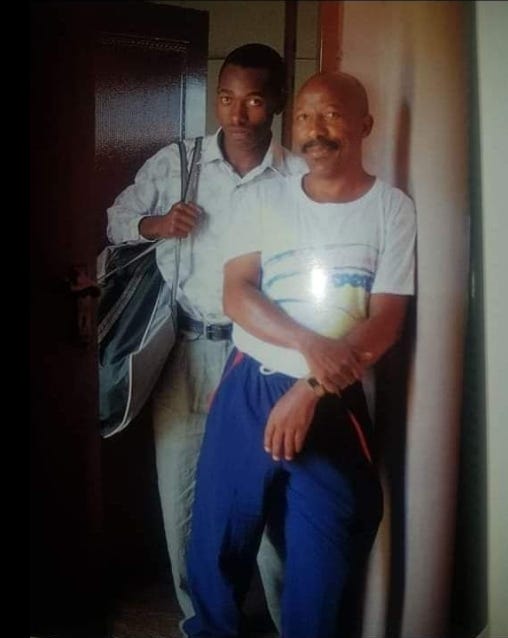

Gus Toyana was not happy with Geoffrey, so he gave his son an ultimatum.

“Either you play cricket or you move out,” Gus Toyana told him.

Gus had raised Geoffrey around cricket and cricketers. When Geoffrey was two years old, Gus and his friends changed his nappies on benches at cricket grounds. Gus and his friends would take turns to care for the baby when a match was on. Gus loved taking his boy to matches. Geoffrey was practically weaned using the sport.

Around the same time, Graeme Pollock moved from Eastern Province to Transvaal (Gauteng) for a job opportunity. By then, Pollock was convinced that his career was over. A few years before, Graeme Pollock, Mike Proctor, Dennis Lindsay and Peter Pollock had staged a walkout in a Republic Day celebration match at Newlands. It was Rest of SA vs Transvaal.

Pollock and his teammates wanted two black players, top cricketers, to be included in the SA side due to tour Australia later that year. Mike Proctor opened the bowling on the day. He bowled one ball to Barry Richards and they walked off. Not a lot of people were impressed.

"I realized that the politics were not great," says Graeme Pollock when speaking of the walkout. "We were ostracized by a lot of people for it (the walkout). They said we should stick to sports and not dabble in politics."

When he got to Transvaal, Ali Bacher convinced him to play for Transvaal. Pollock agreed, thinking that he would just play for a couple of seasons. That was to be the beginning of one of the best eras for the province.

Across town, cricket was dying. The 1970s were a sharp contrast to the booming 50s and 60s. By the mid-80s it was almost off the map. At the time, cricket was not a glorious occupation.

Fields went into disrepair. Teams were responsible for whatever upkeep of the fields that the council gave them access to. There were no dressing-rooms. There was no sponsorship or external help. Teams were nothing more than a gathering of friends, and the league was very much unstructured.

The cricket played by people of colour led nowhere. There was nothing to aspire to. It also had no financial reward. They were streams that went nowhere.

Despite this, Gus Toyana wanted his boy to play cricket. Young Geoffrey preferred football. On the football pitch, they called him Bricks. He was such a solid defender. No one could pass through him.

“I was a decent football player. I played as a central defender,” says Geoff. “I played first-team football for Orlando High School and even did trials with Jomo Cosmos.”

He probably could have made a career from it, but Gus was not taking any chances. Geoffrey was quickly getting out of hand. He hung around friends with whom he smoked and played dice (dice is a gambling game, illegal, played with dice). It’s a slippery slope.

It is very possible that Gus Toyana felt that the cricket would allow him to keep a close eye on 13-year-old Geoffrey and also help in instilling discipline and focus in the teen. But there was a problem, Geoffrey wasn’t much a fan of cricket. He knew it, understood it and could play a couple of shots, but he didn’t like it.

“I found cricket to be boring. A whole day game was not something that appealed to me,” says Geoffrey. “It got to a point that we planned with my football coach that he would pick me up at 7 am for a 3 pm match on Sundays. My dad and I left for cricket at 07h30. My dad would be mad when he came back!”

Backyard cricket could have helped in making Geoffrey fall in love with the sport sooner. But, the yards in the townships have never been expansive or big enough to accommodate backyard internationals. Also, his four older brothers were otherwise occupied elsewhere, anyway. They never took to the sport.

Street cricket could also have helped. It's fun as there are no expectations. The problem, though, was that in the 1980s, especially the late 1980s, one couldn't just play street cricket in the townships.

"Bakers Mini Cricket was popularizing cricket in the township schools," says Geoffrey Toyana. "But we didn't play when the school was closed. There was no excitement around the sport in the late '80s, there was anger and we were being accused of playing a white man sport."

Besides helping players fall in love with the sport, street and backyard cricket are vital for skill development and mastery.

Whether it's cricket or football, 'street sport is a world of unpredictable, eclectic challenges,' as author Tim Wigmore puts it. As part of the book, Elite: How The Best Athletes Are Made, Wigmore investigated the benefits of informal play in skill development.

“The rules, surfaces, pitch sizes, number of players and a player’s individual position all constantly change, which can turbocharge learning,” Tim adds.

With less direct instruction or coaching, street cricket helps players with problem-solving. And they do it while having fun. Young Geoffrey Toyana wasn't having fun when he went along with his father to play for a whole day. But Gus was not worried about the fun element, he was more worried about his son’s future.

Gus Toyana’s boys, the older ones that did not like cricket, got in trouble with the law at one point ao another. He wasn’t taking chances with this one. So asked him to choose between fun and home, he chose home.

“You know, playing cricket saved my life,” Toyana says. “Most of my childhood friends are either in jail or dead.”

Ray Jennings has worked with young cricketers since the mid-1990s. He knows a thing or two about young talents.

“From 19 to 22, some talented cricketers get this idea that the world owes them something,” says Jennings. “Geoffrey didn’t have such an attitude. He didn’t get ahead of himself. It was easy to see his father’s influence on him.”

Jennings and Toyana first met in 1996. Jennings was the Director of Cricket for Gauteng Cricket at the time. Geoffrey was just fresh off the plane from England.

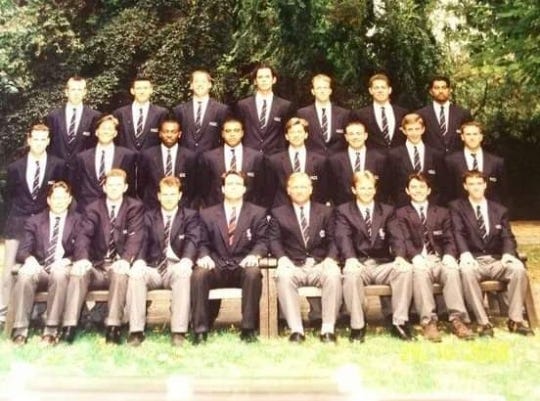

The MCC runs a program at Lord’s, the MCC Young Cricketers program. The MCC YC. Young cricketers that attend the program under-go a six-month program of specialist coaching and intensive competition at Lord’s. Some of the players that have attended the program are Ross Taylor, Mark Waugh, Phil Tufnell and Ian Botham.

According to Lord’s, one in three from each group go on to sign professional contracts with First Class teams. The year before Geoffrey Toyana, 1994, Jacob Malao was a part of the program. He was a left-arm spinner who played for Free State. Malao had a very brief career, playing only 22 First-Class matches and 27 List A matches. Spinners found it hard to get going in his time.

During his time at the MCC, Geoffrey played in as many innings as Malao's entire franchise career. In 25 matches, Geoffery Toyana averaged 55. He was one of the best batters in his group.

“Geoffrey was talented. He had great hand-eye coordination and picked up lines very well,” says Jennings.

“I scored a big hundred against Sussex in one of the matches,” recalls Geoffrey when I ask about his time at the MCC. “They wanted to sign me, but I missed home too much.”

On his return, Ray Jennings took him from Soweto Cricket Club to Old Parks. In 2001 Geoffrey joined Jennings at Easterns. The last thing he did for Gauteng was he scored a title-winning 63 in 2000. In 2003, Jennings and Toyana lifted a title as coach and player. In the final against Western Province, Easterns was 20/5 early on. Geoffrey had a match-winning 120-run partnership with Pierre DeBruyn.

“Ray Jennings taught me a lot both as a player and as a coach,” says Geoffrey. “One of those things was mental toughness.”

Being a young black cricketer in the 1990s and early 2000s, being mentally tough came in handy.

“Geoffrey was a student of the game, just like his father,” says Dave Nosworthy. “He was one of the hardest workers that you would find. He was always working on his game.”

And like his father, Geoffrey was left-handed and batted at number four. Sometimes moving down to five.

“He liked to play his shots,” Ray Jennings reminisces. “He played a beautiful cover drive. He also played with a lot of flair.”

The flair and batting left-handed contributed to his called the Soweto Brian Lara. It wasn’t too far off, like Brian Lara, Toyana played a few big knocks in his time. Around 1994/95, before the name was a thing, Geoffrey had an opportunity to bat with Brian Lara when he visited Soweto Cricket Club and was part of a coaching clinic.

They batted together for almost an hour. A bit of Lara must have brushed off onto the young star. In 1998, Geoffrey was the star attraction for the locals when the SA Invitational XI side played against West Indies at Soweto Oval. Few had any idea who Brian Lara was. For once in his career, Lara was in Geoffrey’s shadow.

During the 1999-2000 season, Geoffrey became the first black African to break into the top 50 run-scorers list in South African first-class cricket. In the 2003/04 season, he was ranked 19th on the list.

Geoffrey Toyana was also a little useful with the ball. He started off as a part-time medium pacer, as most youngsters are wont to be. Later on, he changed to offspin. He has 12 First-Class wickets to his name. Stephen Cook and Dane Vilas are some of his victims.

Geoffrey Toyana started coaching in the late 90s. He was still playing at the time. It was part of a Gauteng Cricket program that encouraged players to coach in the townships where they came from. Partly to grow the game and also to help them earn a little more because they were playing senior cricket on junior contracts.

In his group, there was this one youngster who was always late for training. The boy was very talented and loved his cricket, he was Geoffrey’s best player, but was always late.

“I was always asking myself, ‘Why is this kid always late but all the other kids are there?’”

Geoffrey was unwilling to chalk it down to a lack of discipline or an attitude problem. He had his own situation at the time that helped him to take caution in judging others. To attend the practice at Wanderers, Geoffrey had to take three taxis.

One from Orlando East to Joburg CBD, then another from the CBD to Rosebank. The final taxi was from Rosebank to the Wanderers. Sometimes he could also arrive late. Sometimes he failed to turn up.

“Sometimes mom could not afford to spare money for my transport,” says Geoffrey. “Sometimes, it was a toss-up between me going for training and buying bread. I don’t know how she did it, but she always found a way.”

Geoffrey’s mother earned money through knitting jerseys. His father did the best he could. In the mid-90s, Gus moved to Phalaborwa, where he coached youngsters. Ethy Mbalathi, Dale Steyn and Mandla Mashimbyi are among his students. The distance made things difficult, but the family found a way to make things work. When Gus passed away in 2000, things got worse for the Toyana family.

Geoffrey did his best to contribute to the family finances. He saved as much as he could. On away matches he always chose the cheapest meal option, which was often KFC, because he needed to save as much as he could. Some of his teammates would pass judgement-filled comments about people of colour and KFC. It was degrading.

Instead of judging the young player, Geoffrey decided to play detective and investigate.

“One day, I decided to follow this kid after school. I wanted to see why this guy was always late. He didn’t see me, obviously,” Geoffrey narrates. “I kept following him until I got to his place to see his house only to realize that before he comes to training because he has to cook for his mom first. His mom was HIV-positive and frail. He had to do all those things before he came to training, which is tough."

This has been the cornerstone of coaching, understanding the player and getting the facts right before taking action.

“He knows the game very well. He is a good tactician,” says Ray Jennings who has also coached with Toyana as his assistant and watched his progress through the years. “But his biggest strength is that he understands players.”

Jennings adds that Geoffrey is one of those coaches that is available 24 hours a day.

“He always has the energy for the players,” says Jennings. “A player can call him up at 1 am, and he will be there for them.”

“He is always giving every player everything he can give. He gives his life to cricket, he leaves it all out there,” says Nosworthy, who has coached with Toyana. “One of the most important things in cricket management is trust, and you know you can trust Geoffrey.”

Toyana also gives players the same encouragement that Khaya Majola gave him when he was a teen; believe in yourself. Back your talent and preparation, and everything else will sort itself out. Geoffrey is famous for backing his players.

"It makes a big difference to a player when he feels trusted by his coach and the selectors," says Geoffrey.

Geoffrey Toyana was one of the few black African batsmen on the domestic circuit in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It was a difficult period for a player of colour. It was not odd for a black batter to replace a black bowler, that’s how things worked. A player of colour was the unwanted extra used to tick boxes.

Every match was an audition. One failure meant that one was relegated to the sidelines. Geoffrey understands what it is to be the easy-drop player, to hover on the fringes. He knows what it feels like for the media to question your inclusion in the side at every turn.

He also understands what it is like to be mismanaged. As a player, he was shunted up and down the order depending on the state of the wicket. On batting-friendly wickets, he was pushed down the order.

“Sometimes I would be in batting at seven,” says Geoffrey. “When the pitch was doing quite a bit I would bat higher up the order.”

Without backing from some coaches, he wouldn’t have had a playing career to speak of. The nickname Soweto Brian Lara would probably have never come into existence. Having been backed by people like Jennings and Nosworthy in both his playing and coaching careers, Toyana understands how it is vital.

“We all need someone to believe in us,” he says.

Geoff Toyana chooses to be that someone to his players. He strives to be the coach that he so often wished he had at various points of his playing career.

Jennings concedes that maybe Toyana hasn’t had the same backing he gives players, which is why he hasn’t gotten the right opportunities. He is angry and shocked that Geoffrey, despite doing very well at Lions, one bad season left him jobless for an extended period.

Jennings feels that Toyana, who has coached at every level and risen through the ranks, deserves more.

“It’s horrifying that he hasn’t had the opportunities that he should have had. That irritates me,” says Ray Jennings. "They couldn’t even give him the Under-19 side.”

After Geoffrey himself, Jennings was probably the most heartbroken person that Geoffrey’s coaching career seems to have stalled. He is especially angry at Cricket South Africa for being blind to Toyana’s obvious talents.

“A lot of guys don’t develop and stagnate. Not Geoffrey,” says Ray Jennings. “He is always trying to be better. He has won accolades and yet is always learning.”

Thank you for reading. I am entirely freelance and have no intention of putting content behind a paywall. However, for me to be able to continue producing more content, I depend on your patronage. So, please do support my work on Patreon.

Alternatively, you could Buy Me A Coffee.

Also, please encourage anyone whom you think may be interested in my work to subscribe.