Lungi Ngidi is a big man. He is tall. His heart is bigger. He plays cricket with passion and lives life with compassion and joy.

If you are not a subscriber of Stumped!, join more than a thousand other professional athletes & ex-pros, coaches, commentators & analysts and casual sports fans that receive the newsletter in their inbox each week — it’s free:

At age seven, Lungi Ngidi was a watcher. He was the kid who watched other kids have fun from a distance.

From his position on the embankment, it was like watching TV. Every Saturday morning he picked the same spot to watch the assortment of dreams that were Kloof Junior Primary School’s dads and lads matches. You had dads who were convinced their sons were the next Proteas players, competitive dads out to show other dads that they could have been professionals and dads who came along because their sons made them.

Ngidi's dad was none of these dads. Jerome Ngidi neither played nor understood cricket. He was the school's caretaker. Like his father, Lungi Ngidi had little understanding of the game, he assumed rules as he watched. Whatever the rules were, Ngidi wanted to be a part of this game.

“Every weekend, they'd be there playing and I used to sit in that one spot to watch them,” says Ngidi.

Only a blind person would fail to see the young boy who sat in the same spot week after week. Ngidi did not have to travel far to watch the weekly matches. The Ngidi family lived on the school premises, it was a short walk from their home to the grounds.

“Eventually, one day, I think they noticed that I was always there. So they invited me to come play. That was my first taste of playing cricket. I really enjoyed it, everyone was having so much fun,” Ngidi reminisces.

The game was as fun as he had imagined when he watched from his spot on the embankment. He was hooked. His enjoyment increased as he got better at the game.

The dads and lads matches were his springboard. After that, he had a bigger dream, Ngidi wanted to be picked for the school team. From there it was making the Pinetown and District team - that would prove that he was more than good enough. Ngidi will never forget all the times he received a letter from Pinetown and District letting him know that he had been picked.

“Getting picked for Pinetown and District came with the satisfaction of knowing that I was good enough to be picked for a team other than my school team,” says Ngidi. “That was massive for me, because all I ever knew was playing against my friends at school. So to now play against other kids from other provinces that are just as good or if not better, that really kind of shows you where you fit in.”

Playing for Pinetown and District showed Ngidi that the sky was the limit if he pushed hard enough. Dreams of playing for the Proteas, winning awards and playing at world cups began during his time with Pinetown and District.

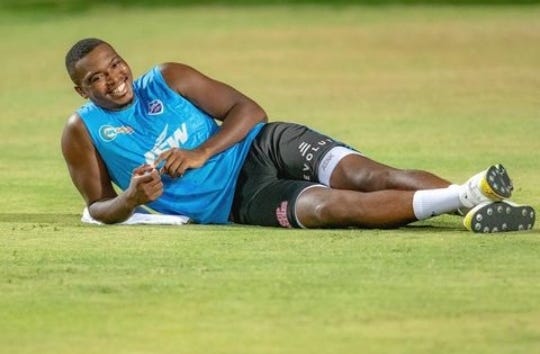

Ngidi smiles because he is living his childhood dream.

“There are only 16 contracted players in the country, and I'm one of those guys. So it just makes me happy to be able to go out there and just play for South Africa, to be honest,” says Ngidi.

Lungi Ngidi wanted to be a batter, but he didn't have the necessary kit - his parents couldn't afford it. So he traded visions of cover drives for aggressive lengths and pace.

In a match for Hilton College against St. Stithians, Ngidi bounced a batter to the hospital and almost broke another's arm. He had batters cowering. He was bowling like his West Indies heroes. He caused mayhem. Batters were relieved to see out his spells.

When he was young, Lungi Ngidi was quick. Properly quick. When Ngidi burst on the Proteas scene, he came with a reputation for banging it in, rushing batters, and bowling aggressive lengths in short bursts. In his debut Test - second innings - Ngidi bowled 12.2 overs for his maiden five-wicket haul (6/39).

Then as his career was picking up, he got injured, as fast bowlers do. He briefly came back. He got injured again and briefly came back again. From 2018 to 2020 Ngidi had problems ranging from hip to abdominal and side strains to knee niggles.

In 1988, Matt Biondi arrived at the Seoul Olympics as the favourite. That was until he finished a disappointing third place in the 200-metre freestyle. In the 100-metre butterfly, Biondi missed on the gold by 0.01 of a second to Anthony Nesty of Suriname. Biondi would later remark that if he had grown his fingernails longer he might have won.

Commentators speculated that there was no way he could come back from such crushing defeats. Martin Seligman knew differently. Matt Biondi was one of the swimmers at the U.S. Olympic trials who had taken part in Seligman’s optimism study.

For his study, Seligman asked each swimmer to swim in their best event. His research team was instructed to inform each swimmer that their swim time was slower by anywhere between 1.5 seconds and five seconds, depending on the length. After a period of rest, swimmers were asked to swim their best race once again.

The pessimists, crushed by failure, found it psychologically challenging to overcome the setback. They performed worse on their subsequent try. The optimists, on the other hand, fueled by failure to perform better, delivered an even better performance on their subsequent try.

Biondi tested in the top quarter for optimism. There’s an old Japanese saying: Fall seven, rise eight. Optimists live that saying. After a disastrous start, by his standards, Biondi went on to win five gold medals in Seoul.

Grit grows inside out for optimistic people. Like Biondi, Ngidi is an optimist.

“When my international career began, everything happened so fast. I never really had that opportunity to plan how I wanted my career to go,” says Ngidi. “Getting injured was a blessing in disguise. It allowed me a period where I got to reflect on what it actually is that I need to do to be successful going forward.”

South Africa produces pacers by the truckload, some of them faster than Lungi Ngidi. Being sidelined allowed Ngidi to reflect on how he had to approach the game if he wanted to fit into any pace trio or quartet that the Proteas needed on the field at any particular moment.

“I had to change the skill that I had at the time. There were obviously guys that could bowl a lot quicker than me. So my focus was control and trying to be able to swing the ball,” says Ngidi.

Ngidi sat at the feet of Vernon Philander to learn about mastering control when bowling and what mindset to have when bowling with a bowling unit where other guys are considered to be the strike bowlers. During his time in the IPL, Ngidi soaked up everything Dwayne Bravo told him about slower balls, yorkers and variations. Charl Langeveldt helped him to perfect his skills.

Ngidi rebuilt his game from the ground up. Ngidi 2.0 emerged. He was no longer express pace.

Lungi Ngidi smiles because he is an optimist.

If you’re enjoying this post, it would be awesome if you shared it with your friends. Thanks, as always, for supporting Stumped!

Good things come in threes. Jerome and Bongi Ngidi took their first plane trip on their first visit to Johannesburg where they stayed in a hotel for the first time.

“I come from very humble beginnings. We stayed in a one-room house in the townships when I was very little,” says Lungi Ngidi.

The Ngidi family, a family of six, moved from the one-room accommodation to a decent-sized house when Jerome and Bongi secured employment at Kloof Junior Primary School. Jerome was a caretaker while Bongi was part of the housekeeping staff.

“Growing up, I wasn't oblivious to anything. I knew the sacrifices that my parents made for me,” says Ngidi. “My parents made me well aware of the financial situation our family was in. I think maybe they just were trying to help me understand that life isn't the same for everyone.”

In addition to his deep love for the game, Ngidi was focused on making it as a cricketer because he realised that the game could be a way for him to improve his family’s life.

“I know what it's like to grow up without money,” says Ngidi. “Those extra benefits that come with a successful cricket career are something that I couldn't ignore. I realized, well, if I become better at this I can improve my family's life. And that's always been my ultimate goal.”

Bongi Ngidi is a giving individual. She makes sure that everyone else is taken care of before she considers her own needs. Lungi Ngidi is like his mother in this respect. He looks after everyone around him first before he turns his attention inwards.

From a young age, Ngidi had dreams of owning a property of his own. Some families hosted Ngidi on weekends when he did not return to Kloof after matches. They had beautiful homes. Ngidi wanted such a beautiful home for himself.

True to form, when he had the means, instead of fulfilling his lifelong dream of owning a beautiful home, the first house that Ngidi invested in was for his parents. He wanted them to be comfortable before he started work on what he wanted for himself.

“You know, people will probably be surprised, even to this day, I don't drive a car,” says Ngidi. “It will probably remain like that until my mom actually decides that she wants one. When she decides which one she wants, then maybe I might think about getting one for myself. I don't really need one right now. So I'll make sure I'll wait until she gets one before I get one.”

Now that his family is taken care of and comfortable, Ngidi is now able to focus on himself. He bought his first house after 2021. He is now able to focus on building a legacy for himself on and off the field.

Ngidi smiles because he can look after his family.

Stumped! is a reader-supported newsletter. Those who opt to leave tips or become patrons are taking an active role in the work that I do by providing vital assistance to bolster my independent coverage of cricket. Feel free to forward this post to family and friends interested in cricket and/or cricketers.

On May 20, 2018, Lungi Ngidi picked up his first IPL Man of the Match award. The previous week he had been in South Africa for his father’s funeral.

"I didn't think I would go back to the IPL after the funeral. I had no intention of going back to the IPL that year." says Ngidi. He wanted to be with his mother and brothers as they mourned his father’s passing. “But my mom urged me to go back. She told me, ‘This is obviously what you've always dreamed of doing. So, you have to go back.’ So I went back.”

In 2002, NBA point guard Chris Paul scored 61 points in a match while grieving over the murder of his 61-year-old grandfather. At the end of the game, Paul purposefully missed a free throw so he would end the game with a point for each year of PaPa Chili's life. It was a great tribute.

In his first match back, Ngidi put on a masterclass. It was the amuse-bouche on the tasting menu that Ngidi was to serve for the rest of the 2018 season. He bowled attacking lines, bowled defensive lines and hid the ball from in-form batters with accuracy and skill. He was on fire. He was still grieving, but he was on fire.

Lungi and Jerome Ngidi were close.

Lungi Ngidi's father did not attend all the matches his son played for the school or for Pinetown and District. But when he did, other parents treated him deferentially, as if he had done something himself. He hadn't. He laid no claim to his son's success. It’s an odd position for a father. All Jerome wanted was to be there for his son.

“My dad never played cricket a day in his life. Even at dads and lads matches, it was pointless asking him to play but he would come watch even back then. That was enough for me,” says Ngidi.

Jerome Ngidi had now joined 'a beleaguered fraternity of watchers and worriers who had been unexpectedly sucked into a world in which they are not proficient.'

“When I first started out, my dad had no clue,” says Ngidi. “Then one day here he was telling me about certain things, wickets, runs, extras and stuff like that.”

Like any other proud parent, Jerome Ngidi had taken the time to learn about his son’s new world. Every time father and son discussed cricket, Ngidi noticed that his father had picked up new terms and his knowledge was a little better than the last time. Ngidi watched his father’s cricket knowledge grow.

“He ended up learning the game entirely, and all of a sudden when I got to the Proteas level he could tell me where I was going wrong,” says Ngidi, who never treated his father like a patzer when he offered advice on what he should have done in a match.

Lungi Ngidi's tribute to his father was a slew of man of the match titles and an IPL trophy.

“That year was just a roller coaster of emotions. You know, having lost probably one of my biggest supporters and then achieving one of my biggest dreams as well. I didn't really know what to feel at the time,” says Ngidi.

Lungi Ngidi smiles because he made his father proud.

There are stories that Lungi Ngidi will always carry with him. Not all of them are good stories.

When his father was a petrol attendant, he saw humanity both at its best and at its worst. He encountered the good, the bad and the ugly. The actions of the ugly left enduring scars, scars that are passed on from one generation to the next.

Jerome Ngidi had one customer who was loath to treat him as a human being so much that when he made the payment, he chose to drop the money on the ground instead of handing it to Jerome. Jerome had the courage to pick himself up after each degrading interaction.

“The stories they shared were eye-opening and painful to hear, because those scars never really close up,” says Ngidi.

The painful stories that Lungi Ngidi carries with him are not just from his father. Others are from former cricketers of colour. When he was a young boy, he looked up to Makhaya Ntini. At one point, his family called him Ntini because of his love for the legend. Back then, Ngidi had no idea what Ntini and others had to overcome to reach the top.

In Makhaya Ntini, Ngidi saw the possibilities for achievement. Ntini broke down barriers for young black players, black players like Lungi Ngidi. After his retirement, Ntini passed the baton of inspiring young minds to Rabada, Ngidi and others.

“I have someone who inspired me. And now I have the opportunity to do that for others. I definitely take a lot of pride in that,” says Ngidi.

When Ngidi speaks about the work still to be done when it comes to these issues, there are those that choose to misunderstand him. They also choose to misunderstand his intentions. They create fresh scars.

But, Lungi Ngidi is not incendiary. He is not driven by bitterness. His parents taught him to be better. They taught him to treat people on merit, not to judge a book by its cover.

Ngidi carries the stories inside him as a reminder of the work that still needs to be done in changing mindsets. In the poem The Pardon, Richard Wilbur says, “I dreamt the past was never past redeeming.” Mankind lives in the desperate hope that past actions can be forgiven. That can only happen if mankind opens itself to bridging the gaps.

"Sweeping these things under the rug doesn't help anyone," says Ngidi, who includes gender-based violence as an urgent matter that needs to be confronted. More than 11 000 women were raped between January and March 2022, the number of women who were murdered is up by over 70%. Ngidi cannot tell you his bowling stats by head. But, he can rattle off these statistics.

Ngidi is part of a group creating a foundation that will help women and children in the fight against gender-based violence.

Lungi Ngidi smiles because he believes in humanity.

When he was a small boy, an anonymous benefactor paid his school fees at Kloof Junior Primary School. The school was upper-class and predominantly white. After he found success with the Proteas and the IPL, Ngidi tried to look for his benefactor. He has never found out who the person was.

“I don’t think my career would have been possible without that person,” says Ngidi.

During his years at Hilton College, Ngidi received numerous donations. Well-wishers came through with stuff like bowling shoes and other sporting kit. Those people’s generosity made his path, which could have been rougher, a lot smoother.

Ngidi has faith that humanity is better than its extreme elements. He has experienced humanity at its best.

“There's nothing that I can say in my cricketing career that I've done by myself. If I did, I'd be lying, honestly,” says Ngidi.

Ngidi has benefited from many helping hands and he wants to be that helping hand for others. He has asked SACA to get him into programmes that help young cricketers. He has come across too many stories of talented cricketers from disadvantaged backgrounds who fall away from the game because they lack support.

Lungi Ngidi smiles because he is a genius. He is a genius at optimism, hope and faith in humanity.

A beautifully written article by our top cricket man Chris. Insight into a mature young man who has his priorities right. Share that smile. We all can.

It's amazing and an incredible story! Well done