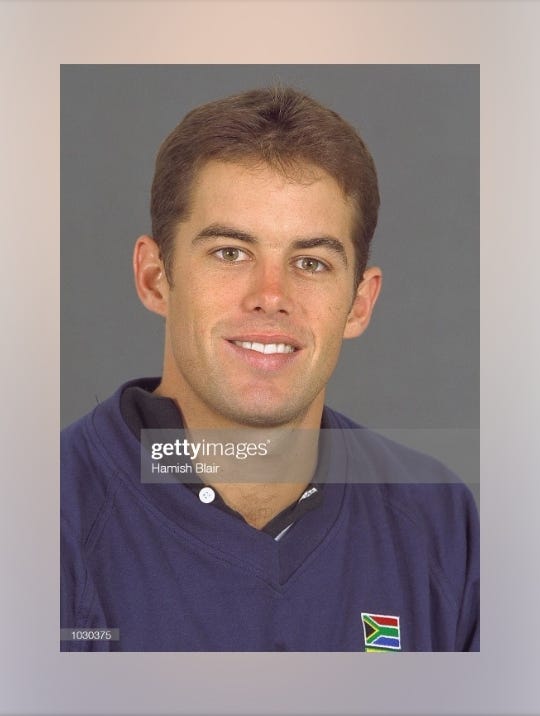

“See you at the close of play,” Mark Boucher had remarked to Neil McKenzie as he headed out to bat after tea on Day 4.

The remark had now become something of a ritual for Boucher. He had started it on the morning of Day 4. As Neil McKenzie and Graeme Smith headed out for the morning session, Boucher had remarked to McKenzie, “See you at lunch.”

“See you at tea,” Boucher had remarked to McKenzie after lunch.

Now Neil McKenzie is six overs away from fulfilling the third part of the ‘agreement’. Light is fading. This is the time when concentration lapses and one makes mistakes as most batters start thinking of the close of play. Neil knows that if the Proteas are going to save this Test, Hashim Amla and himself have to be at the crease the next morning. Losing a wicket now would be less than ideal.

He is on 99. McKenzie looks over at square leg, then at fine leg and then finally at James Anderson as he starts his run-up. It’s the last ball of the 90th over. McKenzie drops the ball to the off-side for a single, and that’s his 100. A very special hundred.

Neil McKenzie raises his bat to celebrate his 100. It’s a salute to his father who was in the stands beneath the scoreboard with the rest of the McKenzie family. They were all supporting him in the same way they had supported his father throughout his career. Neil spent a significant part of his childhood on the sidelines and in the dressing-room of the Mean Machine.

“It’s always nice to get the first one under the belt,” Neil says. “But I think that was a special one.”

It wasn’t his biggest hundred. Just months before, in February 2008, he had scored a mammoth 226 in Chittagong. The Chittagong double century made McKenzie the 21st South African cricketer to score a 200. Almost a month later, he had scored an unbeaten 155 against India in Chennai. This century at Lord’s, a score of 138, was his third-biggest, but it was the more special one.

“There's a lot of traditions that go with a Lord's 100,” says Neil, who has a love for tradition. His children attend King Edwards VII, KES, just as his father did. Neil also attended school at KES.

A hundred at Lord’s is special. But what made this one even more special was that he made it on his father’s birthday. It was a perfect tribute to his hero.

For that century, McKenzie batted for 553 minutes. In that time he faced 447 balls.

“It's not one that I'd like to go back and watch because it wasn't very entertaining. But it was effective,” Neil recalls. “I really had to dig deep. I think I batted for a million hours or whatever, just blocking the hell out of the ball.”

The letter is 21 years old. It feels good to the touch, no one writes letters these days. Neil noticed it by chance, he wasn’t looking for it. He had forgotten that it was still here somewhere. Had he not decided to check what was in this particular box, the letter might have remained untouched for 21 more years. Maybe he should frame it. Suddenly he wonders why he never got it framed.

It’s a congratulatory letter from Archbishop Desmond Tutu. He received it on the morning of his Proteas debut. It was a nice touch. Back in the day, the Archbishop used to pen you a note wishing you well on your international debut. It was a wonderful tradition, it made the players feel that they were a part of something much bigger, something more meaningful.

At the end of the day, it is just a game of cricket, but when you incorporate traditions, it becomes bigger than that. The Black Caps have a cool tradition of their own. On the eve of a Test match, all the players in the starting XI are re-presented with their cap by a special guest. When Devon Conway made his debut, the guest was Phil Neale.

Beneath the Archbishop’s letter is another one from his former KES cricket master, John Hurry. He had also taken the time to write him a congratulatory note on his debut. Hurry was an institution at KES, he coached generations of cricketers.

"Written pen statements from these unbelievable, incredible human beings wishing you well was very special, they are still really special today,” says Neil McKenzie.

The fact that there was a time it didn’t look possible that Neil would play sport competitively made the messages even more special.

When he was eight years old, he got injured. He suffered a broken leg and a shattered knee following an accident in his parents’ garage. It is an accident that had Neil trapped between his father’s car and the workbench. McKenzie had to be hospitalised for two months. He still has some scars from the accident, one of them on his ankle where a nail ripped through his ankle.

“I had some internal bleeding and had to have a colostomy bag,” Neil shares. “I thought it was going to be permanent, the colostomy bag. Thank goodness it was a temporary thing, not a nice experience having that colostomy bag.”

The accident left his leg at an angle. It is something learnt to live with it, and when he turned professional, he learned how to take better care of it and not allow it to be a hindrance, physically or psychologically. A lot of the time he iced it after a long knock. Ice and stretching.

However, he did suffer back issues when he was in his 20s, because of the angle. He managed these with a lot of gym work and rehab sessions.

“If your leg is at an angle it messes with everything in your body in terms of your alignment and all that,” McKenzie says.

Yet, despite this, he led a very active childhood. His father, a proper team man who was part of the all-conquering Mean Machine side, encouraged him to take part in team sports. It is something that he also encourages his children to do, to take part in team sports as much as they can. Neil believes that it helps in making you a better individual.

“I try to impart that same stuff to my kids,” he says. “I don't mind what sport they play, I encourage them to give it a go and not just quit.”

Being part of a team is partly the reason why he has been using GM bats for 17 years, he enjoys being part of the GM team. That and the fact that he never scored an international hundred with any other bat. He trusts the GM bats. This is the other thing about Neil McKenzie, he has little quirks. But it’s not just that he has quirks, he also has OCD, which made his quirks seem a little over the top.

For instance, Neil McKenzie tried to ensure that he didn’t place his foot on a white line whenever he stepped onto the pitch. Stories have been told of him insisting that all the toilet seats were down before he went out to bat.

At one time, his Transvaal teammates strapped his bat to the ceiling. It was their way of getting back at him for strapping their gloves and other bits of kit to the ceiling, creating what looked like chandeliers. That day he scored a ton with that bat. The night before their next match McKenzie strapped his bat to the ceiling. Unfortunately, he was dismissed for nought in that innings. That was the end of the little ritual.

“They used to say I was superstitious,” Neil shares. “But, I think like a sports person, you want to control what you can't control, and cricket has so many uncontrollable parts.”

In evolutionary terms, humans have perfected the skills of gathering and processing information to find regular patterns that help them to predict the future outcome of events. And because of this, we are more likely to repeat actions that we took the last time we were successful at anything. In the face of unpredictability, these actions become more meaningful. Most rituals are born this way because they act as buffers to uncertainty.

“In cricket, you've almost got to rely on a few things going your way,” says Neil. “And I think with the OCD I tried to bend or get the luck on my side or whatever it was. So there were certain rituals that I'd go through to try to make it happen.”

Rituals act as tension regulators. By following a simple ritual, athletes lessen their anxiety in the face of unpredictableness. A University of Cologne study revealed that participants who had lucky charms or had rituals had improved performance compared to when they were not allowed their rituals or charms. They felt more confident about themselves, and thus gave themselves the best chance to perform at the best of their abilities.

Rituals also act as triggers, precursors to actions. Performing these actions puts players in the zone. It is a way of psyching themselves up. As Rafael Nadal puts it, “It’s something that you start to do that is like a routine. When I do these things it means I am more focused, I am competing. It’s something I don’t need to do, but when I do it, it means I am focused.”

And even though the strapped to the ceiling bat ritual was short-lived, Neil McKenzie had one enduring one. Before each delivery, he looked at square leg, fine leg and then at the bowler running in.

Anyway, he loves his GM bats. Other than the GM bats, the only other bat that has a special place in McKenzie's heart is, probably, the Duncan Fearnley 405. It was presented to him by his school after he scored a 100.

“It was presented to me in front of the school,” he smiles. “It was quite special. Can't believe I remember that. That was about 38 years ago.”

It was around the time that he had the accident that left him with pins and his leg at an angle. But, despite the awkward angle that his leg was in, Neil took up his father’s encouragement to participate in team sports as something of a challenge. He participated in almost every team sport that he could, rugby, hockey, was part of the athletics team, cricket and soccer. Neil was so good at soccer that he played for the Southern Transvaal side.

“To be honest, I wasn’t doing too much studying, at the time, just a lot of sports,” he smiles. “My dad used to threaten every time I got my report that I was going to go to a Damelin which didn’t have sports.”

It became sort of a running joke, a threat that was never fulfilled. Cricket is probably better off they were empty threats, we might have never witnessed one of the longest innings - measured by balls - played at Lord’s.

Neil McKenzie takes a brief moment before answering my question. He considers it. He is not so sure that he fulfilled his career as a cricketer. He didn’t play as much international cricket as he would have liked.

“As most batters, you always think you left a few runs out there,” he says. “You always want more runs and think you could have done better or played more games.”

But McKenzie is also realistic about some of the reasons why he didn’t play a lot of international cricket. After being dropped from the Proteas side after his initial run, it was harder to break into the side again. There was just so much talent it was hard to displace anyone.

“There were a lot of players that were in the side getting runs in,” he says. “You had Herschelle Gibbs, you had Graeme Smith and you had Hashim Amla. Hashim Amla was making his way through the team. You had Jacques Kallis, I wasn't going to kick him out. Ashwell Prince was averaging in the 40s. I think AB de Villiers was five. And he was a youngster. Yeah, he obviously hadn't been averaging 50, but he had just turned the corner.”

McKenzie’s career might not have gone the way a young Neil would have imagined when he received his first Proteas call up while in a queue at Home Affairs. Being dropped from the side at 28 and spending almost four years on the sidelines is the last thing that he would have even remotely considered.

He had also never imagined that some of his highest scores and crucial knocks for the Proteas would come with him batting out of position. Before his second coming to the Proteas, McKenzie preferred to bat in the middle order.

“Mickey Arthur and Graeme Smith, they wanted to build a side where they've got good team men, good team players,” he says. “And they chatted to me for a bit. They wanted me to bat three at one stage. That didn't work out. And then, you know, the only spot available was the opening berth and they said, “Listen, you can do it, would you give it a go?” And jeez, look who doesn't want to play for South Africa? So if that's the only spot available, you know, I jumped at the chance.”

It’s not the script he would have written for himself, but he is content with the way things turned out.

“I am very grateful for the second chance that I got to play for South Africa,” says McKenzie, who feels privileged to have represented South Africa. “The game has given me too much to look at the negative side of things. And I think that’s why I am content with my career and playing 20 years of First-Class cricket.”

It is possible that the century at Lord’s also has something to do with these feelings of contentment. In many ways, that English summer tour was a portrait of who he was as a player: resilient and the ultimate team man.

Thank you to everyone who has shown their appreciation of my work and this newsletter. I am entirely freelance and have no intention of putting content behind a paywall. However, for me to be able to continue producing more content, I depend on your patronage. So, please do support my work on Patreon.

Alternatively, you could Buy A Coffee.

Also, please encourage anyone whom you think may be interested in my work to subscribe.