Stuart Broad has retired from international cricket, and one of his last actions was on brand. Broad is a creator of moments. Mid-way through the 43rd over of Australia's first innings, Broad strolled to the stumps, flipped the bails around and then replaced them in their grooves. On the next delivery, Marnus Labuschagne edged the ball to Joe Root at slip.

It was Mark Wood's wicket. Joe Root's catch. But it will be remembered as the wicket that came after Broad fiddled with the bails. It's a very Broad thing. Broad didn't invent the celebrappeal, yet it will always be associated with him. Stuart Broad was the Johnny Appleseed of the celebrappeal and now, he just might help with the spread of bail switching.

On day one of the last Ashes Test, Australia was on 91 for one and England was struggling to make a breakthrough. Broad had an inkling he had seen either Ricky Ponting or Nathan Lyon fiddle with the bails before. Like England, they couldn't buy a wicket. After they did it, they were rewarded a wicket. Broad was convinced swapping bails was an Australian ritual.

But, bail-swapping isn't an Australian ritual. I couldn’t find a record of Ricky Ponting doing it, but Nathan Lyon did do it at least twice. The most memorable moment was in the fourth Test of the 2019 Ashes at Old Trafford. With England 163 for two, Joe Root and Rory Burns having put together a 138-run partnership, Lyon switched the bails at the non-striker’s end and turned them straight back round again. The trick seemed to work: Burns was out after scoring just two more runs, and Root after three.

Australian ritual or not, it also worked for Broad. Or it seemed to work, and that is all that matters for other cricketers to copy it. It doesn't matter that Marnus Labuschagne has a thing with bails. According to legend, when he was a junior cricketer, Labuschagne was dismissed when the off-bail toppled because it was insecurely placed. Since then, Labuschagne has resolutely checked that particular accoutrement is properly placed before each ball. Anyone fiddling with his bails is enough to upset his focus.

This newsletter is completely reader-supported. If you’re willing and able, please consider supporting it in one of two ways, leaving a tip or becoming a Patreon. Thank you so much for your time and investment.

Cricketers are notorious for latching on to eccentric behaviours that seem to shift things in their favour. They will eat the same breakfast on matchday because the one time they had an omelette and toast they had a good game. Many batters wear the same clothes in the same order for the same reason. Cricketers will not move from their seats when a teammate is close to a milestone for fear of disturbing the vibe or something. Most cricketers’ shirt numbers are linked to lucky breaks.

Jordan Hermann’s preferred number was seven. One day he forgot his shirt in his hotel room and a teammate, Simeon de Bruyn, lent him his playing shirt. De Bruyn wore the number six. Hermann scored 176 with the number six on his back. After that match, he decided to keep the six because it had brought him luck. He now wears the number 76 shirt. David Bedingham wears the number five because he survived a life-threatening accident on the fifth of December.

Some batters face the exact number of throw-downs as part of their pre-match routine. If they are dismissed for a low score, most batters will go through a checklist of rituals and routines, wondering which one they had forgotten to play out, or if they did their main ritual properly, to the letter. Superstitions and rituals are so ingrained in the game that as a fan and cricket writer, I feel like I have spent the bulk of my life bemusedly watching cricketers do little ‘non-cricket’ things, some of them odd, to help their game.

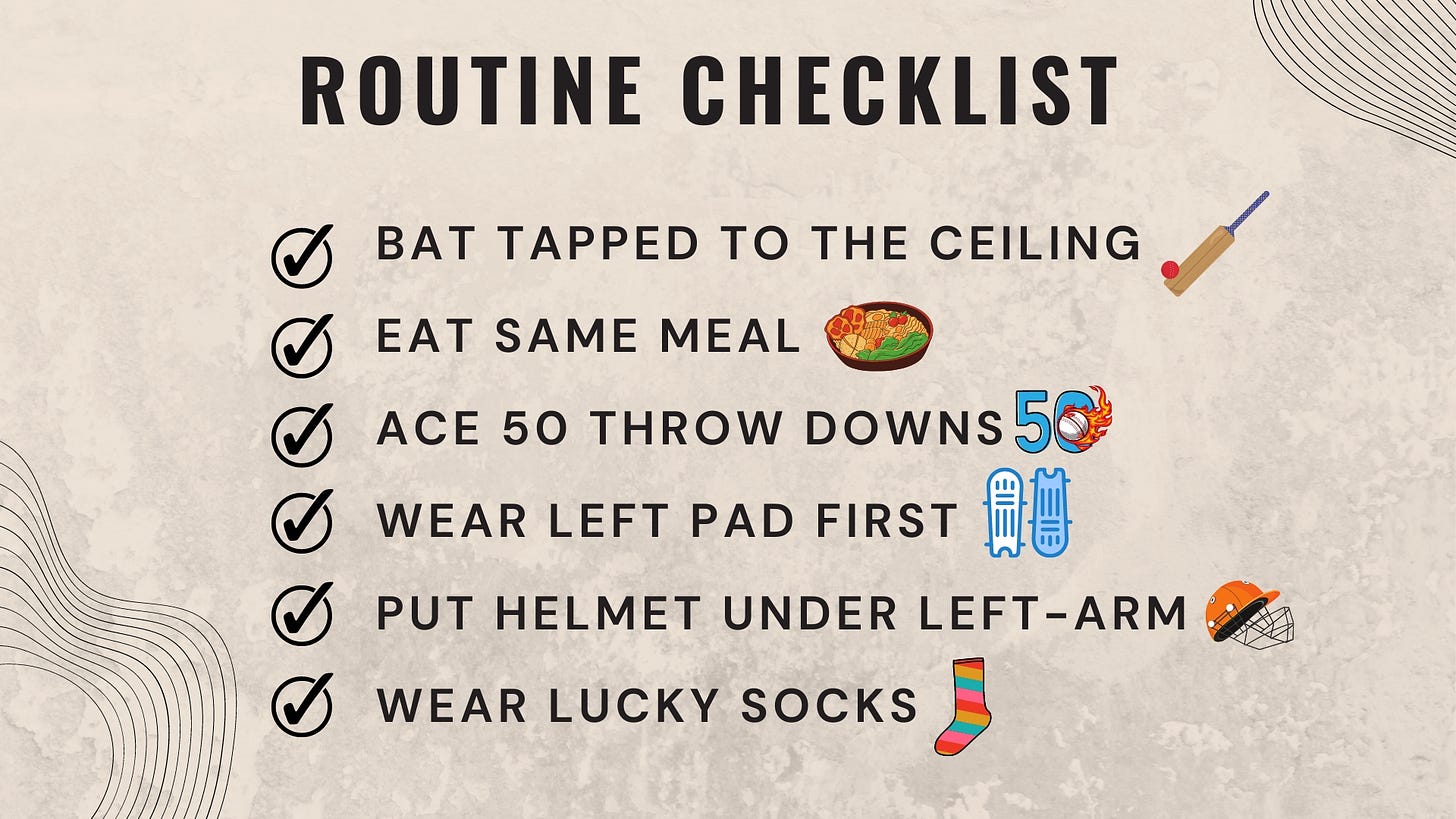

In 1950, B. F Skinner taught pigeons how to play games that include table tennis, miniature bowling or playing simple tunes on a toy piano using pellets and other food forms as rewards for specific actions. One time, he decided to switch things up. He wanted to see what would happen if he gave the pigeons pellets every 15 seconds regardless of what they did.

Skinner found that the birds formed associations between specific behaviours and receiving food. If they tucked their head under a wing, hopped from side to side or turn in a clockwise direction, the pigeons repeated the actions when they hoped to be fed the pellets.

Like Skinner’s pigeons, human beings are wired to behave in the same way. It’s an evolutionary trait. Humans have perfected the skills of gathering and processing information to find regular patterns that help them predict the future outcome of events. Keis Ohtsuka, a senior lecturer in Psychology at Victoria University, suggests that because of this, we are more likely to repeat actions that we took the last time our team was successful.

Cricketers tend to believe there is a causal connection between two events that are linked only temporally. For a brief period, Neil McKenzie had a thing with bats strapped to the ceiling. McKenzie used to get irritated with his teammates because they often left the dressing room immediately after a match. McKenzie was raised in the Mean Machine dressing room and back then players bonded and learned from each other over post-match drinks.

To get back at them for the ‘abandonment’, McKenzie resorted to strapping their pads, gloves and other gear to the ceiling where they hung like chandeliers. One day, it was McKenzie who had to leave early because he had an event to attend. As punishment, McKenzie’s teammates strapped his bat to the ceiling. After taking it down the next morning, McKenzie scored a 100 and thus began the ceiling bat-strapping that is now associated with McKenzie. He stopped it after he got dismissed for nought despite it.

McKenzie’s brief flirtation with strapping his bat to the ceiling is one of the rare instances where players abandon a ritual after a short tryout. In his experiments, Skinner found that once a pigeon associated one of its actions with the arrival of food or water, sporadic rewards would keep the connection going. One bird, which associated hopping from side to side brought pellets into its feeding cup, hopped 10,000 times without a pellet before it gave up.

Like the pigeon, McKenzie had other actions he held on to whether he played well or not.

“I think as a sportsperson, you want to control what you can't control. You know, you've got a high-pressure situation you want to make runs in the final or your team's in trouble you and you're desperate. I think in cricket, you know, you've almost got to rely on a few things going your way and I think with the OCD I tried to bend or get the luck on my side or whatever it was so there were certain rituals that I'd go through to try and get my way,” says McKenzie.

Around 1915/16, social anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski moved to the Trobriand Islands for two years. According to Malinowski, Trobrianders felt the same way about their fishing magic. Among the Trobrianders, fishing took two forms. In the inner lagoon, fish were plentiful and there was little danger; on the open sea, fishing was dangerous and yields varied widely. Malinowski found when fishing on the open sea, Trobrianders did not leave anything to chance. Before a trip to the open sea, they performed rituals to ensure safety and increase their catch.

Like the Trobrianders, most cricketers prefer not to leave anything to chance and use routines, rituals and other odd behaviours as insurance against the uncertainty that’s built into cricket. Bowlers have watched as their best deliveries narrowly miss the stumps or are edged a few millimetres beyond the fielder and run to the boundary. Batters have watched in disbelief after being dismissed by half-trackers and innocuous deliveries that they play blindfolded on any other day. In addition to skill, luck plays a role in cricket.

Gregg Steinberg, professor of human performance at Austin Peay State University and author of Full Throttle, wrote, "For athletes, there's this unpredictability in sports. They never know how they're going to play, how the other team is going to play, so when you do something superstitious, it gives you a greater sense of control."

Routines, rituals and superstitions give cricketers a sense of control over the elements of chance that surround the sport and they will try almost anything to do so. This, in turn, gives them confidence. And that is all that matters in professional sports, confidence. Confident players do well more often than not.

Stuart Broad tried something he had seen someone do in the past and it worked. I see bail-swapping being adopted by other players. Speaking of rituals, there is only one ritual that I have never seen or heard other people replicating; Beth Amm's wicket-inducing ritual. Beth Amm was known to light up a cigarette when her team needed a wicket.

Beth supported Salem, a Port Alfred team that takes part in the Pineapple Week cricket tournament held in the Eastern Cape annually. Her husband and two sons played for Salem. If an opposition batter looked in good touch and was giving Salem a hard time, Beth would write their name down the side of her cigarette in pencil. By the time the cigarette was smoked, legend has it, the batsman would be snuffed out.

If you found this interesting, please share it:

You can support Stumped! by leaving a tip:

Thanks for reading. Until next time… - CS