Predicting The Future: What Stands Out Average or Strike Rate?

A player's average shows you what they have done, and their strike rate shows you what they can do, and it is from that that you deduce potential.

Player A has an average of 50 and a strike rate of 48. Player B averages 44 and has a strike rate of 57. Which player do you think has better prospects in the future?

Cricket fans, writers, selectors and a lot of other interested parties often try to peer into the future and predict how well a batter will do in the future. That future could be promotion to franchise level, promotion to international teams, selection for tournaments and so forth. And because almost everyone concerned doesn't have a crystal ball to consult, we look at the numbers.

How many 100s and 50s they have, and probably most importantly, the average. If anything, the average is the go-to metric, because it shows consistency. On the strength of this reasoning, Player A has a very bright future.

But, is it the right call?

As I mentioned previously, too many averages are influenced by not outs, and as Hoffie Lemmer wrote in his paper (Team selection after a short cricket series) traditional batting averages can be misleading. This is not to say they have a role to play, just that they need help.

A better metric would be a high batting average and a high strike rate, or an average batting average and a high strike rate. And definitely not a high average coupled with a low strike rate. In fact, the strike rate should be the first consideration followed by the average.

High Strike Rate

The future of cricketers is not so much as predicted by their results as much as it is predicted on the basis of what they promise. Averages are a definite sign of results and strike rate is what shows their promise, more than anything else.

Care needs to be taken here. By high strike rate, I am not referring to players who just throw the bat at the ball, the sloggers. Sloggers will have a high strike rate and a low average. They do not necessarily have a wide range of shots that they can play with control.

One of the strangest things about players with a high strike rate and a decent (or good) average is that they are often dismissed because of poor shot-selection, not because the delivery was very good. The term often used is, "threw away their wicket..."

This is the group where Player B is found.

In fact, a player with a higher strike rate will face more bad balls than a player with a lower strike rate. That's because a player with a wide range of shots can easily turn a good ball into a single. By so doing, by diminishing the number of unplayable deliveries a bowler can bowl to them, they get the bowler bowling to their strengths.

Another thing, a high strike rate is not simply a function of hitting boundaries and sixes, but also taking singles and running twos and threes. A player with a low strike rate often has a very high dot ball percentage, which increases the danger of being bogged down to the point that they are unable to wrestle back control from the bowlers. This is as important in Test cricket as it is in limited-overs.

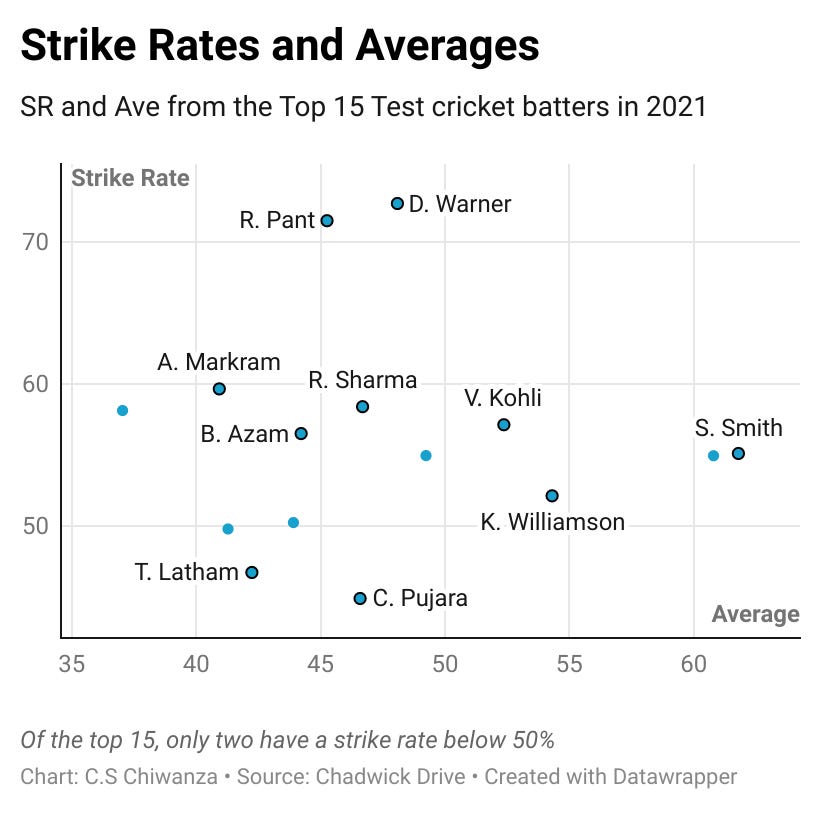

This is even more important in this "new age" of Test cricket. The format is evolving and moving at a quicker pace than it did in the past 10 to 15 years. A look at the format's top batters really speaks of the direction it has taken.

[Granted, there are times (in Test cricket) when batters need to blunt the attack, but they also need to possess a wide enough range of shots that allows them to change gears and move the game ahead. If anything, players with range can easily adapt to such needs and circumstances.]

Sloggers also tend to have a high dot ball percentage.

Consider AB DeVilliers, he has such a wide range of shots he seems to create new shots while batting at the crease. The truth is, he modifies shots from his wide range. And one of the most common things many commentators have remarked on is DeVilliers' ability to run between the wickets and rotate strike. He does not sit around waiting for the bad ball. Doing so would make him a sitting duck.

Cricket, the contest between bat and ball, is a battle for control. When the batter waits for the bad ball, then the bowler has no control of the innings, whether it's ODIs, T20 or Test cricket. The only way that a batter can seize control is through influencing the batter into doubting their plans. And that is only possible if the batter can diminish the number of good deliveries a bowler can bowl.

A favourite example of mine is Adam Gilchrist.

When he was England coach, Duncan Fletcher would place a whiteboard and marker pen in the corner of the dressing room, on which he would write the plans for the opposition’s batsmen.

The notes would be detailed and often incisive, except where Adam Gilchrist, the Australia wicketkeeper, was concerned. Instead of some tactical insight, next to Gilchrist’s name there was just a question mark.

Times have changed and with the help of advanced analytics, coaches can now zone in on player weaknesses quicker. But the point is that with his insanely high SR of 81.95 in Tests, Gilchrist was not easy to bowl to. His range of shots put pressure on bowlers.

Batters with a wider range of shots in their armoury adapt better to different bowlers and conditions and can modify their shots much better to find more scoring options, compared to their counterparts with a lesser range.

Facing the same bowler bowling the same variations, the batter with a higher strike rate will face fewer "impossible" deliveries than their counterpart with a low strike rate.

Adaptability

For years, four scientists from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands conducted what is now known as the “Groningen talent studies.” The team, led by Marije Elferink-Gemser, tested soccer players who were in pro-team development pipelines each year for a decade, starting with twelve-year-old boys in 2000.

One of the findings they made was that no matter the training, the slow kids never catch up to the fast kids in sprint speed. And in the words of Justin Durandt, manager of the Discovery High-Performance Centre at the Sports Science Institute of South Africa: “We’ve tested over ten thousand boys, and I’ve never seen a boy who was slow become fast.”

Slow kids never make fast adults.

(This is not to suggest that speed cannot be taught, it can, however fast kids and slow kids respond differently to training. Therefore, while the slow kids can never be fast, they are always going to be faster than those without training.)

Given the same training, the same facilities and equipment, instead of the gap between the slow kids and the fast ones gradually decreasing, it gradually increases. Instead of practice making similar, it has been found that in instances like this, it makes even more different. Instead of convergence, there is divergence.

The same is true for batters with a wider range of shots in their arsenal and those with less. Common knowledge tells us that practice has the capacity to close the gap in performance. If two people have equal access to the same training and facilities they should, at some point, draw closer in their ability. Therefore, two batters with equally good coaching and similar facilities and equipment should improve at the same rate. This is not so.

By virtue of having such differences in the range of shots, their adaptability to changing match situations and conditions also differs. The player with less range is less adaptable. Also, while it may sound a bit harsh, they have less trainability. The fact that they have a limited stroke range past a certain age shows that they have limitations in trainability. And past a certain age, it is just difficult to teach new strokes.

To return to the Groningen talent studies, you can train a fast kid how to manage and sustain their speed much more efficiently depending on conditions, and they will remain fast or become faster. Similarly, a batter with range can be trained on clever execution and modification of shots. Not only that but with modification of their shots they also increase their range of shots. They can only get better.

Perspective

Back to Player A and Player B. Player A will reach a plateau much sooner and is prone to suffer a phenomenon that I can only refer to as "failure to launch." Player B on the other hand has the ability to adapt and grow as they have the range. In other words, Player B has more upside potential compared to Player A.

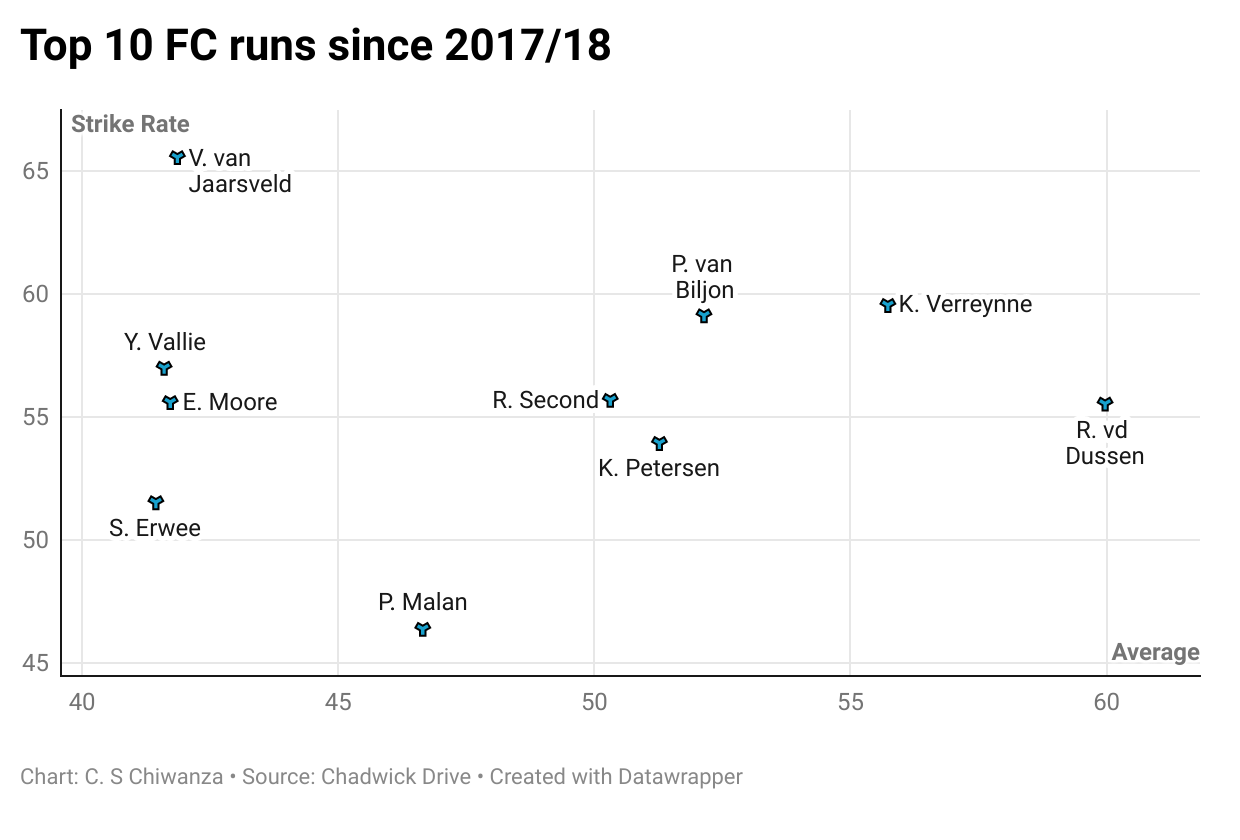

For instance, Kyle Verreynne with his high strike rate which hovers just below 60% (59.94%) in 4-day cricket, proves that he doesn't struggle against bowlers in those leagues and even though there is the potential of regression as he gets accustomed to Test cricket, it is unlikely to fall below 50% against better quality bowlers. In fact, his strike rate is at par or higher than that of international cricketers when they face the same bowlers in domestic cricket.

Compared to another domestic player with a higher average but lower strike rate, Verreynne would be a better pick for international selection on the basis of his upside potential.

A similar argument can be made for Rahmanullah Gurbaz participating in the IPL. So far in his career, Gurbaz boasts impressive figures: an average of 32.18, a strike rate of 153.08, a boundary rate of 25% and a non-boundary percentage of 52%. Even though his figures are from T20s and T20Is against lesser lethal bowlers like those in the IPL, his statistics show range. He isn't a slogger and has a higher boundary percentage than players like Virat Kohli and Ben Stokes by a distance. Therefore, when you factor in the possible regression that comes with facing a higher calibre of bowlers, it does not look like he will fall behind the likes of Kohli and Stokes in boundary percentage.

Do you think this content is worthy of your support?

If you think so, you can Buy Me A Coffee. Alternatively, you can buy several coffees if you like (simply change the number of coffees to your preferred amount). All coffees you buy will be greatly appreciated.

If not, worry not. I am consistently working to improve the quality of both the content and delivery. In the meantime, do you think it’s worthwhile for you to contribute to that growth and development by buying me a coffee?

Another way to help: please encourage anyone you think may be interested to subscribe to this newsletter, the blog or both