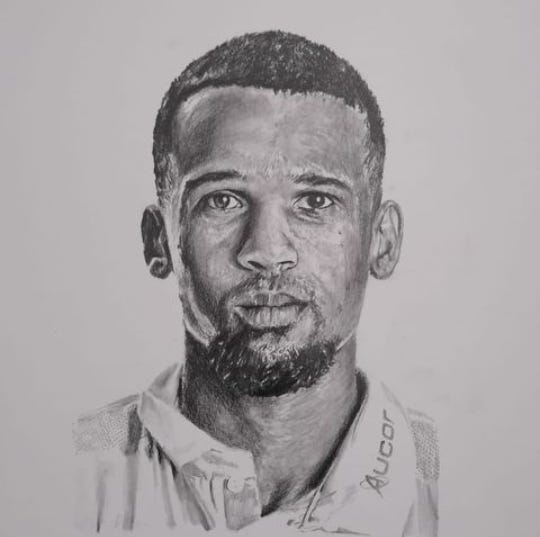

“If I’m only remembered as a cricketer, I’ve done a bad job in life,” says Lizaad Williams.

Williams is one of the few to make it out of the small town he is from. Not many do. Many just become what they grew up seeing, fishermen and fisherwomen. As one of those that made it out, Williams sees it as his duty to show the youth from Louwville and the greater Vredenburg area that there is more to life than what they grow up seeing around them.

On April 3, 2019, Williams graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of the Western Cape. He plans on furthering his studies. Williams hopes that his cricket and academic achievements will inspire more youngsters from his hometown to dream big.

If you are not a subscriber of Stumped!, join more than a thousand other professional athletes & ex-pros, coaches, commentators & analysts and casual sports fans that receive the newsletter in their inbox each week — it’s free:

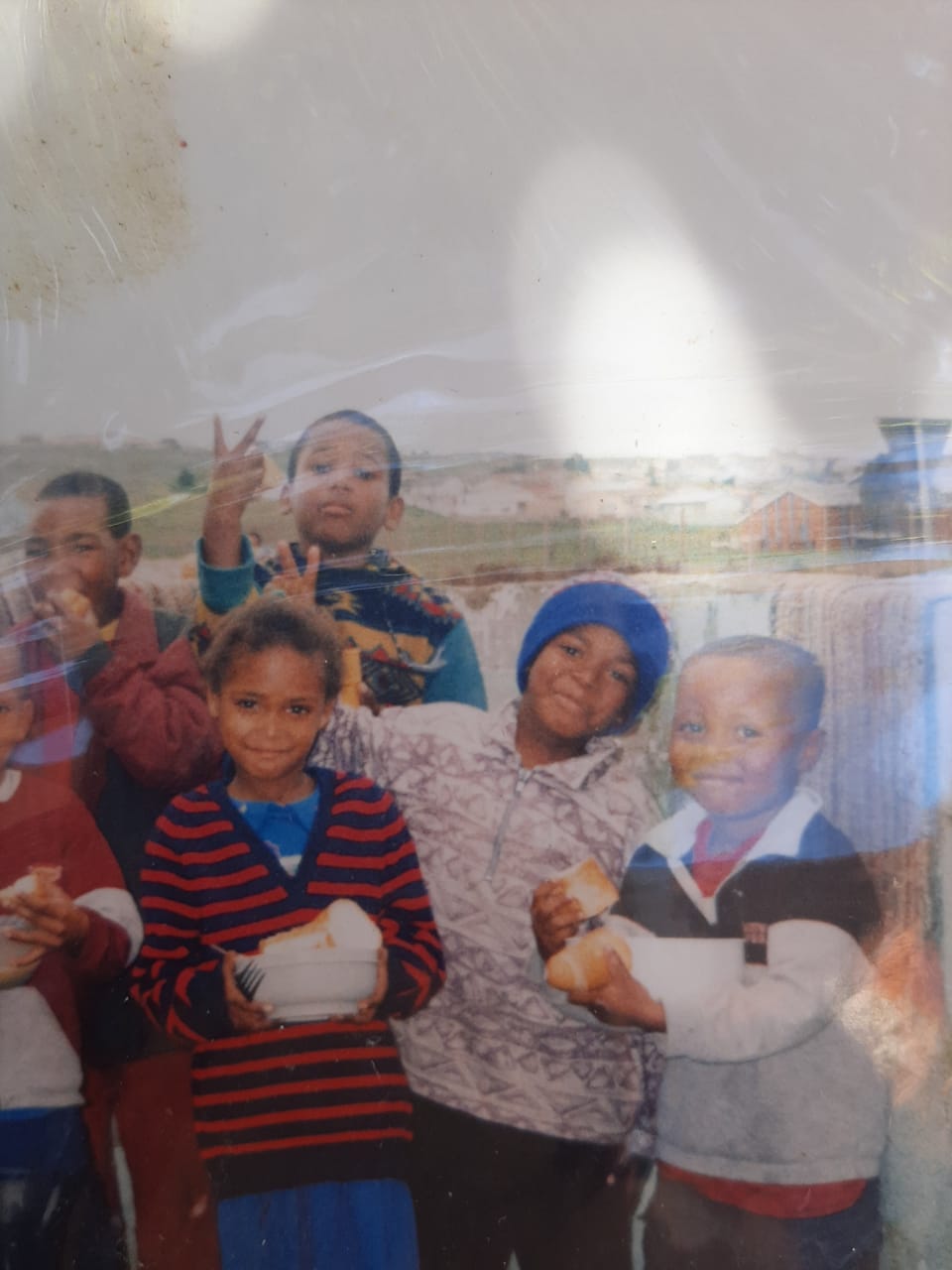

Play clothes, shorts and t-shirts, underneath school uniforms. That is how the boys dressed. Sometimes layering clothes in summer or warm weather can be uncomfortable, but the boys did not mind that. Lizaad Williams was one of those boys.

When he shed his school uniform, Williams turned into Tollos. Jacques Talmakkies, or Tollos, as everyone else called him, was a local rugby star. Talmakkies was no Jacques Fourie, the Springbok centre of his day, neither was he Lukhanyo Am, but he was the best centre Louwville had seen in a while.

Tollos was strong defensively, was a good runner in support of his fly-half and was excellent at recovery. The role was demanding, and Tollos executed it like no other club player for miles around. That is no small feat, considering that in Vredenburg rugby was a religion. Do well for the local cricket club and you become a star, but do well for the local rugby club and you become a legend.

In Vredenburg, you were least likely going to run into residents talking, like experts, about the tactics and the personalities of Jacques Kallis, Neil McKenzie and Ashwell Prince. But everyone had an opinion on what the Springboks ought and ought not to do. Everyone also had an opinion on who was the next best local rugby player.

A few adults liked the look of young Lizaad Willaims. The boy had a fire in him. He did not back down from a fight. Williams got into scraps, came out with bruises and remained unfazed. He was willing to make sacrifices for victory.

“Rugby was not just a sport for us,” says Willaims. “It was a way of life. Club players actually felt like that's the way of giving back to the community.”

Williams certainly saw himself as a future Tollos, so he inherited his hero’s nickname. Every kid from Louwville did that, they picked names of older rugby players from their community and attempted to replicate their exploits on the field.

“Rugby was my first love,” says Williams. “It made me feel part of something bigger than myself, you really felt camaraderie amongst your teammates.”

Lizaad Williams turned the page. He was ready for the game. His job as the scorer was to update the scoring book. His station was on the veranda. A chair and table on the veranda. When there was some wind, Williams struggled to keep the scoring book on the right page and make the entries at the same time. The adults, the players, updated the scoreboard by the clubhouse.

Scoring was a duty that 11-year-old Williams enjoyed. It made him feel like a part of the team of adults playing on the field.

He did not have cricket dreams at the time, but he enjoyed being part of the action. Williams always turned up at the matches because his uncle brought him along. Willaims’ uncle was a second-team player for Vredenburg-Saldanha Cricket Club. All he wanted was to share his love for the game with his nephew.

“He would come to pick me up every Saturday morning when it was cricket season,” says Williams.

Williams and his friends were always on the lookout for disused cricket bats. They were not easy to come by. The cricket community was small and the players used bats until they broke, then they would repair them. When they eventually let go of them, they were too far gone for any sort of repair. These were the bats that Wiliams and his friends used them they played street cricket.

The bats always made an appearance in the rugby offseason, or when there was a big game on TV, the Proteas playing against a team that captured the attention of a few.

Williams and his playmates lived in a cul de sac. The street was a circle. It was here that they played street cricket. Their version of street cricket almost mimicked gully cricket. In the subcontinent, gully cricket is played in an alley. Most points are scored when you hit the ball straight past or over the bowler. It was the same for Wiliams and his mates.

Hitting the ball into someone’s yard was a dismissal. Hitting a window was a dismissal for the whole crew, and they would not regroup for at least a day or two. No one wanted to face the wrath of an angry auntie. All aunties knew how to curse and swear, they also did not hesitate to give you a hiding before dragging you to your parents. Everyone respected - and some feared - the old aunties.

The least risk was in hitting the ball straight. But, hitting straight is a skill that requires one to be technically sound. Williams was not technically sound as a batter. All he knew and could do was to hit across the line.

“I can't remember an innings that lasted longer than 10 balls,” says Williams.

Lizaad Williams was the young energetic boy who was always running up and down the expanse of the field picking balls. He was also present at the nets, again, picking up balls. That is how Esmond Barends knew Lizaad Williams.

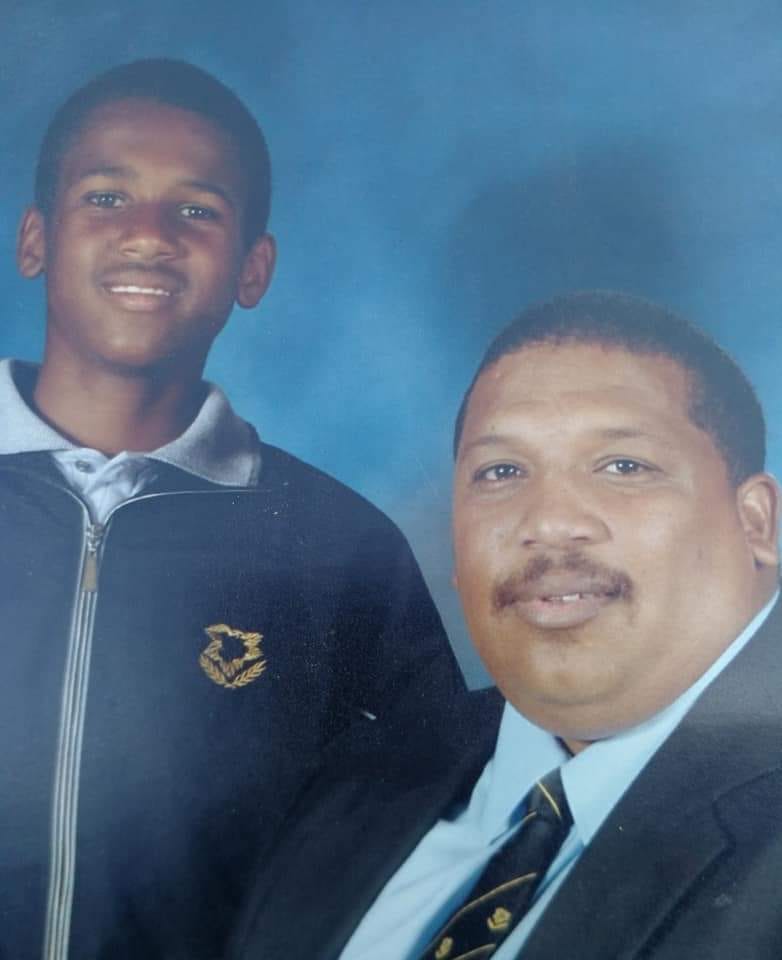

Barends also knew Williams as the youngster who went to the same primary school as his two sons. Sometimes the boys played together. Williams was also the talented kid that his teachers consistently spoke about. Williams excelled at rugby and soccer and was very decent at cricket. Barends taught and coached at Weston High School, so he decided to keep a closer eye on the boy.

“I played first-team cricket for Vredenburg-Saldanha CC and Lizaad used to attend practices and games just to watch,” says Barends. “I always enjoyed chatting with him. He showed great maturity for a small boy. He was very ‘smart’ compared to his peers.”

“I started playing club cricket at a young age because of Mr Barends, he saw something in me,” says Williams.

Williams had a fire inside him, a competitive streak that more than made up for his youth when he played against older and more experienced players. A fire that has not dimmed as he has grown older.

“Lizaad has that passion and that desire to win. You can’t coach that. It’s either in a player or it’s not. He’s certainly got it,” Proteas head coach Mark Boucher has said of Williams. “He’s one of those guys who, if you’re in the same team as him, you love playing with him. You know he will be by your side and has got your back. But if you’re in the opposition you probably hate playing against him.”

That dog fight and aggression in Williams were nurtured during his club cricket years. As early as 13 years old, Lizaad Williams was playing first-team cricket for his club, Vredenburg-Saldanha Cricket Club. The adults didn’t give him a pass because he was younger. He had to pull himself up to their level.

“It was like being thrown into the ocean and getting told to swim or drown,” says Williams. “I learned to give back as much as I got.”

Barends made it his business to see to it that Williams never missed out on any opportunities.

“One time, Lizaad had to attend a camp somewhere, and during the period we also had our tests at school,” says Barends. “So we had to let him and another boy, Duwayne, write the test at school at 06:00 o’clock in the morning. In another instant, I had to get the exam question paper to his coach so that he could write the test on the day that the paper was written at the school.”

Barends made it his business to see to it that Williams had the necessary equipment, whether he was playing for Weston High School (before his move to Huguenot), Vredenburg-Saldanha Cricket Club or Boland junior teams. Barends also made it his business to see that Williams had transport to attend trials and matches away from Vredenburg.

“For provincial commitments, we had to travel to Paarl which is 150km away from Vredenburg ( in total a drive of about 300km ). During some weeks we had to drive to Paarl twice or trice a week,” says Barends.

Barends did this with money from his own pocket. When he could not meet the expenses, he reached out to his colleagues at Weston High School and local businesses. The Vredenburg community always pulled through for Lizaad Williams. He never missed a single camp or trial he had to attend.

Stumped! is a reader-supported newsletter. Those who opt to leave tips or become patrons are taking an active role in the work that I do by providing vital assistance to bolster my independent coverage of cricket. Feel free to forward this post to family and friends interested in cricket and/or cricketers.

Huguenot High School is not a cricket talent factory. It is neither Wynberg Boys High nor Grey College. Like Lizaad Williams' hometown, Vredenburg, it does not boast alumni that went on to become Proteas players. It was difficult for Williams to see himself as a professional cricketer because he did not know anyone like him, from where he was from, who had made a career out of cricket.

Williams did see himself as a rugby player, though. He had dreams to play for Boland Rugby Union. Like every other Louwville youngster, Williams believed that rugby would be his way out of Vredenburg. That would be his ticket out.

Mervin Green had done it. Green worked for South Africa Rugby Union for 20 years. Tythan Adams signed with Western Province at 16. It was possible. Williams cradled that hope for as long as he could. He played Craven Week before he let go of the dream.

“Lizaad was in grade 11 when I had a stern talk with him and actually asked him to stop playing rugby and focus on his cricket. He was already in the ‘system’, which provided him the opportunity to launch a professional career,” says Rosseau Mercuur.

If anyone could convince Williams to focus on cricket, it was Rosseau Mercuur. Mercuur was a father figure to Williams. He took up that role the afternoon he visited the Williams home in Louwville in 2007. That afternoon, he promised Williams’ mother, Lizette, that he would look after the boy as his own.

Mercuur had met Williams a few weeks before his visit to the Williams’ home. He had watched Williams outperform and outwork every bowler that attended the Under-14 tournament held at Huguenot High School. The boy had a higher work rate than the other kids. He also bowled faster than the average youngster of his age.

What Mercuur did not know was that Williams had only started bowling that year. Before then, he had been a wicketkeeper. Williams was okay as a keeper, the problem is that he found it less exciting with each day that passed. However, if you bowled fast enough, aggressively enough, you could send the batter cowering. Williams liked that idea.

When Mercuur showed up at the Williams home to talk to Lizette Williams about a cricket scholarship her only worry was about her son’s welfare. Her son was about to venture into a world foreign to him. This was different from a situation where Lizaad Williams stayed over at a school for a handful of days during the course of a tournament.

Williams had never lived away from home. There were not many kids from Louwville who enrolled at Huguenot High School, most just went to the local day school. Vredenburg was home to factory workers and fishermen and women. People who could not afford to send their children to boarding school.

“90 to 95% of families from my community have the same background,” says Williams. “We all had the same struggles. I don’t think they are any different to the struggles of many South Africans. Maybe we were different in that where I come from fish is the main source of income and it is also the main source of nutrition.”

Huguenot presented Williams with a different challenge from what he was used to. Lizette Williams was worried about her son’s ability to cope in that environment without any support structure.

“That afternoon, as I sat down in their simple living room, I assured Lizette Williams that I would also take care of Lizaad in this new environment at Huguenot High School. I made a commitment that I will guide, nurture and look after him,” says Mercuur.

If you’re enjoying this post, it would be awesome if you shared it with your friends. Thanks, as always, for supporting Stumped!

It was like a social media Reels clip. But in a loop. The ball is short of a length outside off stump, Taskin punches it to gully and the ball's flying to Wiaan Mulder's right. Mulder takes the catch on the second attempt after the ball pops up behind him.

The memory, only a couple of minutes old, kept playing on Williams’ mind as he walked back to his bowling mark. This is what he had always dreamt of, playing Test cricket. It is the most difficult format. It is the format he has always wanted to play. More importantly, he now had wickets in all three formats. Williams’ maiden ODI wicket came off his first ODI delivery.

Not too shabby for a youngster from Vredenburg.

At the top of his mark, Williams adjusted his sleeve. The Proteas medical team had opted to cut his shirts downwards along the seam from his left armpit. Williams had developed a skin irritation that was aggravated by his playing shirt. The cutting open was to avoid more chafing. This is the shirt he was going to frame, his mother would have seen the funny side of this.

Williams stood on top of the letters ‘T. U.’ It is a habit of his, he marks his run-up with the two letters. It’s short for Thank U (you).

It is a thank you to his mother. She was his rock for a long time. When life threw curveballs at him, Lizette Williams was there to encourage him to keep going. It's not about whether you fall, but whether you have the strength to rise after a fall, she taught him. Lizette did not know much about cricket, but she was her son’s number one supporter.

Williams became a father just before he turned 17, as teenagers do if they play around with girls without protection. Maintaining a balance between fatherhood, school and cricket, Williams made the Coke Week team that year. It was his second appearance at the tournament. Like Keegan Petersen, Williams was part of the Boland Coke Week team three years in a row.

The next year, Williams captained the Boland team at Coke Week. One of his greatest achievements was beating Western Province. There is a healthy rivalvry between Boland and their ‘Queen’s English-speaking’ neighbours.

It is also a thank you to Rousseau Mercuur. Mercuur kept the promise he made to Lizaad Williams' mother. It is also a thank you to the rest of the staff at Huguenot High School.

“We had a values-driven and caring approach towards Lizaad, who sometimes was rebellious and perceived as arrogant,” says Mercuur.

It is a thank you to Esmond Barends. He was there at the very beginning and he stuck around. It is also a thank you to the Vredenburg-Saldanha Cricket Club. The club cricket prepared him for the next level. It provided the balance Willaims needed during the time he played high school cricket.

It is also a thank you to the game that gave him a career.

“It is to say thank you for the opportunity to play cricket. It is a privilege to play the game that I love,” says Williams. “Every opportunity I get to play, whether it’s club cricket or whatever level means a lot to me. I’m just thankful to play the game of cricket.”

T. U

T. U to everyone for reading this article. A bigger T. U to everyone who supports Stumped! and every one part of the Stumped! family. Joining the Stumped! family is easy, it’s only a click away.

I am entirely freelance and some very nice people help me to continue producing more content by donating a little here and there. Some do so by supporting my work on Patreon.

Others prefer to leave tips:

Others also support sharing posts that they enjoy. You can do all three.