The ODI World Cup is not going anywhere, at least for the moment. The 50-over World Cup is still the highest-earning ICC event and the current ICC heads are the generation that made the format great. If the 50-over World Cup is to disappear, it will not be before 2027. South Africa is on track to host that one. India and Bangladesh are in line for the 2031 edition.

With that in mind, I had a look at what South Africa could do to give themselves the best chance at winning the World Cup at home.

Rassie van der Dussen has an insane ODI record. He has been so good that he is worth two slightly above-average batters for the Proteas. The Proteas haven’t had a batting number seven in years, and van der Dussen has had to play the dual role of a number three and a number seven. He has done it well.

Quinton de Kock and David Miller are in the top 50 ODI batters of all time. Miller is one of three players with at least 100 ODI caps who average above 40 and have a strike rate of over 100. The other two are AB de Villiers and Jos Buttler. No other batter has taken command of the number five/six slot like Miller.

De Kock, on the other hand, is the most destructive opener South Africa has had in ODI cricket. Not only that, his ODI average is in the top five for South Africa. When compared against other openers from his era with 4,000 or more ODI runs, de Kock has the third-best strike rate.

Temba Bavuma has been incredible in recent years. He just seems to get better and better. He is the second South African batter after Herschelle Gibbs to carry his bat in an ODI game. He scored a century in the process. Bavuma found the cheat code of ODI cricket.

Heinrich Klaasen announced himself to ODIs in pink with a blistering knock against India. He followed that up with performances that fell below his expectations. But that was because a lot was happening, he couldn’t play his natural game because of the mixed messages he received from the selectors.

In 2021, Klaasen decided he was damned if he played his natural game and damned if he didn’t. So he decided to play his natural game, and it freed him. He has shown again and again that he is a force in white-ball cricket. One of the best middle-order batters at the moment.

This newsletter is 100% reader-supported. If you’re willing and able, please consider supporting it in one of two ways, leaving a tip or becoming a Patreon. Thank you so much for your time and investment!

The 2023 ODI World Cup is the last time this band plays together at a major ICC event in the format. De Kock announced his pending retirement. He doesn't see himself at the 2027 ODI World Cup. It's also hard to see any of the other guys at the next World Cup. Miller, Bavuma, de Kock, van der Dussen and Klaasen have an average age of 33.25 years. In 2027, they will have an average of 37.25.

I have always been of the same view as Jos Buttler, who declared, "If people are still performing, age is irrelevant,” after England’s average age at the 2023 ODI World Cup was brought up. These guys, Miller, Klaasen, Bavuma and van der Dussen, can still add value, but holding on to them on that basis, for victories in bilateral series, is short-term thinking.

In isolation, bilateral ODIs are meaningless. However, they get context from being used as a tool to prepare for an ODI World Cup. As such, South Africa should use the new ODI World Cup cycle that kicks off in November/December to prepare for the next one. The vision needs to be bigger than the next series. For cricketing reasons, the 2023 ODI World Cup has to be their last dance in the format.

When people study successful teams, the aim is to unearth counterintuitive gems that can be attributed to their success. No one studies dynastic sides in the hope of being told that conventional wisdom is the key to their success. This is one of the reasons why the All Blacks are a favourite study for many - they have unconventional things like the Haka that have always added to their mystique.

And yet, even though there are moments where counterintuitive truths have helped teams here and there, most successes are built on a foundation of common sense. Most times, it is the most obvious cricket things that bring success. Catches win matches, scoring more boundaries than the opposition gives you a better chance at success and no, three twos are not equal to a six.

When the ECB commissioned Nathan Leamon to study what factors predict World Cup success, they probably hoped for counterintuitive truths. Instead, Leamon’s report stated the obvious. Three obvious factors predict World Cup success: batting strength (much more so than bowling), a winning record and experience.

The winners of the 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011 and 2015 ODI World Cups all had one thing in common: they were one of the two teams with the highest scoring rates in the years leading up to the tournament. Also, except for the 2011 World Cup, the tournament has been won by teams that came into the tournament seeded in the top two. In the 20 years between 1995 and 2015, only one team that made the World Cup finals did not have an experienced team in terms of ODI caps.

Armed with that information, England selectors asked two simple questions before selecting a player for each bilateral ODI: 'Is this player still going to be at the 2019 World Cup? Does the player play the way we want to play?' If the answer to both was no, the player was nowhere near the squad. They identified a core of youngsters and backed them, making sure that they played as many games as possible.

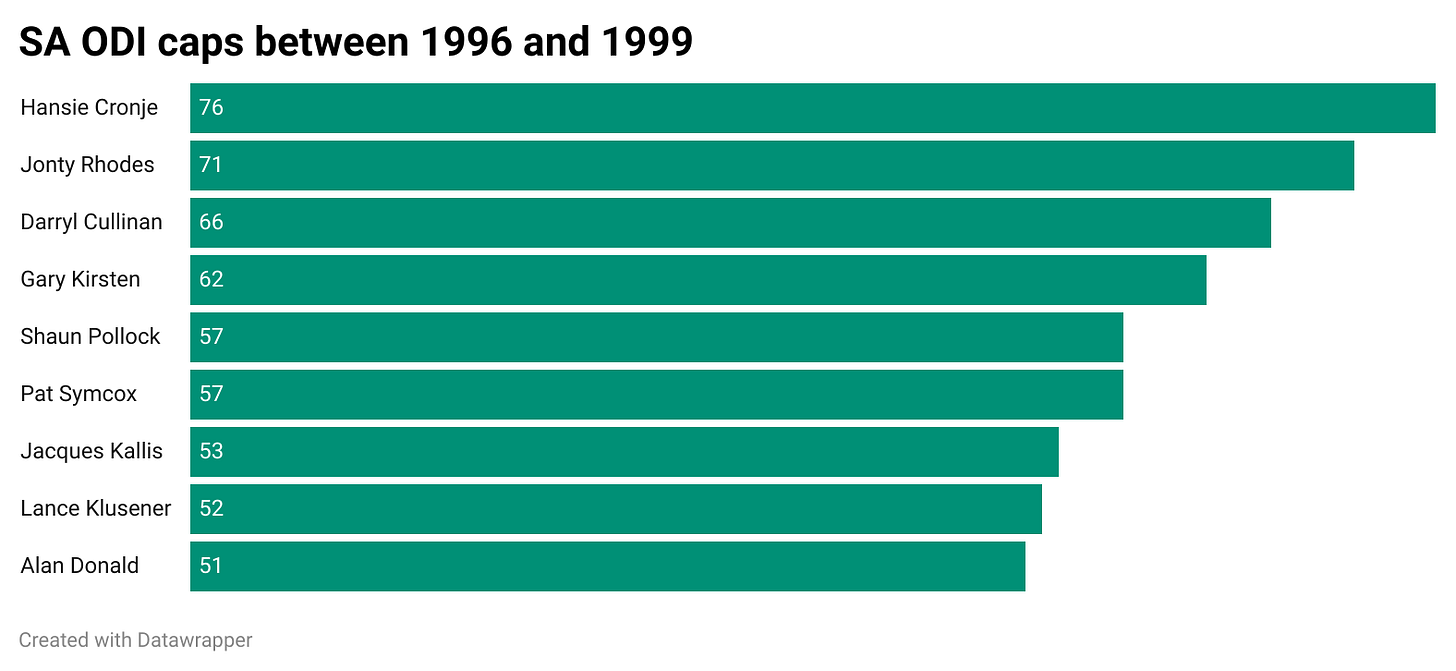

What Leamon found was so obvious it should have been common knowledge. One of the things Bob Woolmer would have liked in his ideal preparation for the 1999 ODI World Cup was for all players in his starting XI to have close to 50 or more ODI caps by the time the tournament came around. He almost managed it. Nine of the players who took part in South Africa’s 1999 World Cup campaign averaged 61 matches between them.

When I had a chat with Rob Walter, he said he wanted his batters to be more attacking. That is what it takes to close the batting gap between South Africa and leading countries. In the decade starting 05 January 2020, the Proteas are third behind England and India in ODI strike rate. England leads with a hefty 6.12 runs an over, India has been going at 5.98 runs an over, while South Africa was going at 5.90 runs an over - their run rate jumped to 5.99 runs an over after the series against Australia. His words were, “Our philosophy is to assess where the game is at and take the most positive option relative to the match situation.”

This new approach closes the gap. And given that batting strength has a strong bearing on how well a team performs at ICC events… Anyway, here is another conventional truth - it is easier to develop a style of play over a longer period, years not months. The longer players are encouraged to play a certain way, the more it becomes their default setting. Continuity in selection also breeds confidence and players develop a better understanding of their roles in the side.

South Africa has 30 ODIs plus the Champions Trophy between December 2023 and the 2027 World Cup. The Champions Trophy should serve as a checkpoint to gauge the progress in World Cup preparations. One of the Proteas’ best World Cup campaigns, the 1999 World Cup, came on the back of a 1998 Champions Trophy win. The 2027 World Cup is the Proteas' Mount Olympus, the Champions Trophy is a stepping stone to getting there.

South Africa has been consistently good, but never great. In 1999 and 2015 they tittered on the brink of greatness. This is their moment to take the step up from being a good side to great, their one chance to shrug off the ‘chokers’ tag. They have four years to work towards it. The sooner they embark on the quest, the better.

To build a great side, one that just doesn’t play a great brand of cricket, but has a good shot at winning trophies, South Africa's journey has to start now. Their last match at the World should be the story where one story ends and another one begins.

If you found this interesting, please share it:

You can support Stumped! by leaving a tip:

Thanks for reading. Until next time… - CS