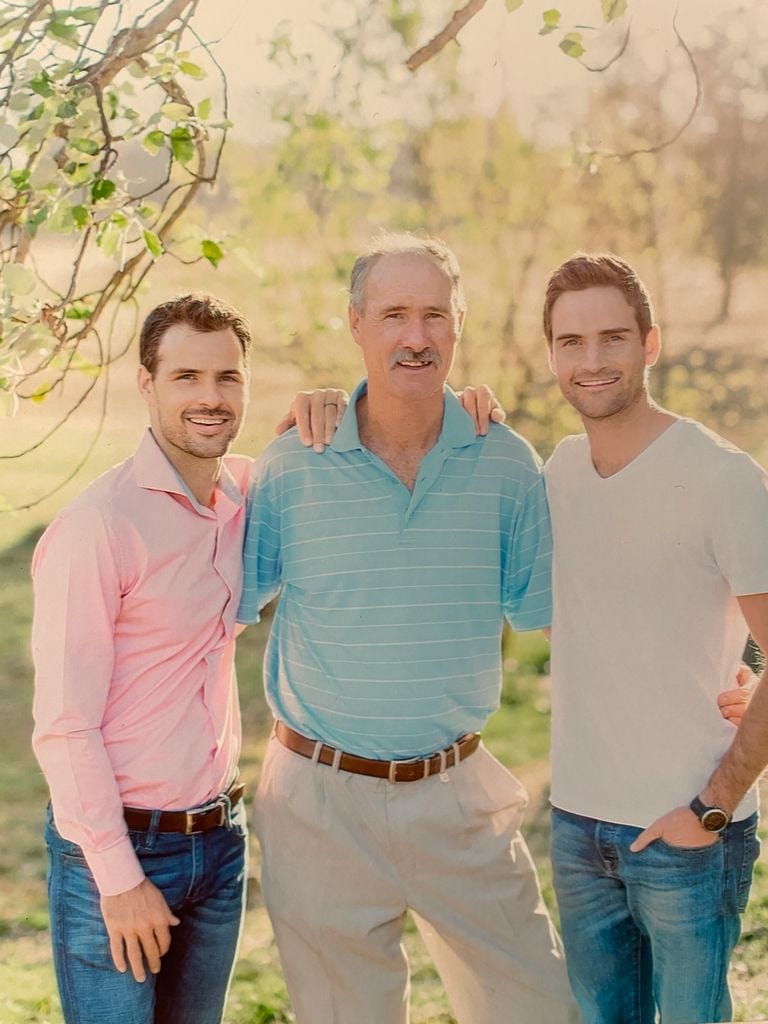

Century on Debut: Stephen Cook

Stephen Cook's debut for South Africa was a moment that helped him emerge from the shadow of his father's brilliance

On 22 January 2016, Stephen Cook became the 100th male player to score a century on debut with his 115 against England. He became the 5th South African to achieve that feat.

As he remembers it, the last person outside of the Proteas squad whom Stephen Cook spoke to moments before his debut was his father, Jimmy Cook. It’s a lovely memory, and Stephen distinctly remembers the words.

"You know, my boy,” Jimmy told him, “if you don't get out first ball you have done better than me. No pressure."

It was hardly a pep talk, it was a challenge.

“Dad was my hero, so anything that he had done, if I could get any one up on him, I suppose that was an achievement of itself,” Stephen smiles.

In a strange way, that is the story of Stephen Cook in cricket, he always wanted to get one-up over his hero, that way, he could be seen as his own man.

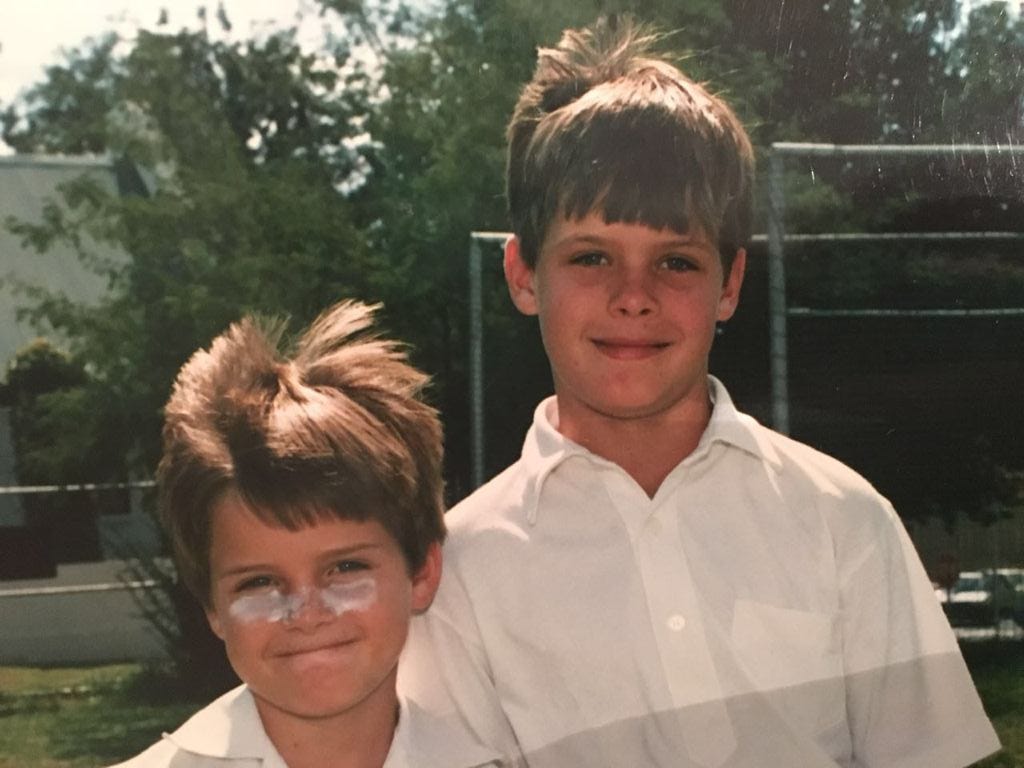

Stephen grew up on the grassbanks of cricket grounds, at the Wanderers, mainly. His early memories are about that: on grassbanks playing cricket while his father was in action in the middle. If anything, Stephen struggles to remember a time when he wasn’t at a cricket ground or when cricket was a part of his existence. If there was such a time, it is blurred from his memory. It is like walking, I mean, there was a time when we couldn’t walk, but how many of us can remember that time?

Ask him about what he remembers about England from when he visited the country in 1989, and the first thing that comes up is the Somerset cricket pitch. He was seven and his father had signed up for Somerset.

“I can remember countless of those long English summer evenings,” he smiles wistfully, “playing on the outfield after the end of the day's play with my brother, with my dad. The members, there watching while having a pint at the pub after the game. I have very good memories of those days.”

It didn’t matter where it was, the grassbanks were his second home. When he was not on the grassbanks, Stephen was in the changeroom, rubbing shoulders with professionals.

“That was just how things were,” says Stephen. “All the kids, whether it was the young McKenzies or the young Jennings or the young Cooks or young Rice kids, we were all in the change-room, in and amongst it during the heat of battle.”

But, that was a different time for cricket, a different era. While the overseas clubs might have paid a little more than the local ones, there wasn’t a lot of money in it. As Stephen explains it, ‘there were no private schools.’ They were a regular family. It is quite different from the life that a modern international player can give their family. I mean, they were comfortable, but definitely not affluent.

Stephen was educated at IR Griffith Primary School, a government school. And, like any other ambitious young athlete he wrote a pile of applications for bursaries to private schools later on, looking for high school placement. That didn’t pan out. Fortunately he was accepted at KES, King Edward VII School, which has a good cricketing background and pedigree.

Anyway, besides the lack of money, Jimmy Cook’s era was also far from today’s standards of professionalism in other ways. What the sons and daughters of modern professional cricketers would experience in today’s change-rooms, if they are given entry, is very different to what kids of Stephen Cook’s time experienced. everything was so… disorganized. Guys seemed to be figuring things out as they went along.

Yes, it was called professional, but it resembled more a Sunday league than it did a professional one. There were no formal coaches, just guys who could play cricket getting together and forming a team.

Team meetings were held over beers at the Wanderers pub in the evening after everyone had knocked off from their main jobs. That's how it was. There was so little organization that on away tours, it was most likely that (maybe) a manager and a captain would run the show.

As far as fitness was concerned, players were left to their own devices. Stephen’s father, who was a teacher at Fairways Primary School at the time, would do his fitness training early in the morning, running and stuff, before he took his kids to school and went to work. He would teach and coach sport till 4 o'clock in the afternoon, and then walk up the road to Wanderers and try to get a net in before the sun went down.

“Dad sacrificed a lot to be able to play cricket,” Stephen admits with audible admiration. “You can imagine working a normal teaching job, people out there know how hard teachers work. It's a great profession. And then to try and hold a cricket career together on top of that. He would take a leave to go and play an away 3-day game.”

Stephen inherited his father’s love and dedication to cricket. Jimmy was careful enough to not push his son into the sport. As a sports instructor at school, he encouraged his son to take up as many sports as he could and be active. So, Stephen making a choice to pursue cricket for himself warmed Jimmy Cook’s heart. It was more than he could have hoped for. The result was that the father spent countless hours throwing balls to young Stephen, teaching him technique and still keeping it fun enough for him to retain interest in the game.

“My dad would take me to the nets,” Stephen fondly recalls. “He would shoot to me on the bowling machine and helped me forge those early parts of my technique. But, for the most part, it was mainly about enjoyment.”

One of the things that stuck out in Stephen’s mind about those training sessions was that whenever his father took part in their backyard Tests, he gave the boys extra points for hitting the ball to the offside. He wanted his son to be a strong offside player. Jimmy Cook felt that that would help him become a better player should he become a professional cricketer, which is something that Stephen had decided on. He was convinced that he would play for South Africa at some point.

“From an early age I sort of had these visions of following in dad's footsteps, probably naively so,” he laughs.

It was one of those big, audacious goals, the type that many probably never get a chance to fulfill. You see, for one thing, Stephen was a late developer - a bit of a small kid, small for his age. And even though his father could teach him technique, he really couldn’t teach him strength. He was one of those kids who could hit a sweet cover drive for the ball to only roll a few meters.

“I couldn't hit a 4, you know, I couldn't hit a boundary,” he laughs. “I would play some wonderful cover drives and get singles. I would get home proud to tell my dad all about it. My dad would ask, ‘How many did you score today?’ I would reply, ‘Dad, I batted the whole 25 overs of the Wednesday afternoon fixture for 23 not out.’ And you would see dad shaking his head thinking, ‘Oh, that's not looking good my boy. I know you're happy, but that's no good.’"

The late developer trait is a constant in Stephen Cook’s career. When he debuted for the Proteas, he was the oldest bloke on the field. That doesn’t happen often. That as it it may be, Stephen Cook credits his late bloomer status for his incredible debut.

“It certainly helped that I was a little older when I debuted. You see, I was a little more mature then,” he shares.

There is something that just makes late bloomers perfect for Test cricket, a quality that few young debutants possess. Not only do they have an acute awareness of their game, its strength and weaknesses and how to navigate it. They also possess equanimity. Equanimity is a “mental calmness, composure, and evenness of temper, especially in a difficult situation.”

Equanimity is one of the by-products of growing older. You see, as people grow older, they become calmer. There is a change in the way we relate to our environments as we grow older. This change gives us a better ability to deal with stressful situations better. There is also resilience. Late bloomers develop resilience through years of striving, a lot of trial and error, and knocking on doors repeatedly for years.

I don’t know any other format where these skills are more critical than in Test cricket.

Another reason for his late development was that his parents did not allow him to exclusively focus on cricket until he had completed his studies. They tried, as hard as they could, to see to it that he did more than just play cricket. His education came first and they encouraged him to explore and experience other avenues just as much as he did cricket. His father was so set on this so much that he blocked his selection to the Gauteng senior side at one point.

“I was writing my Matric exams when I got picked for Gauteng, in the provincial team,” he says. “And my dad phoned the selectors and withdrew me from the team. He said, ‘Stephen is writing his Matric exams, he needs to finish his exams. When he finishes his exams, he's available for selection.’"

No words can explain the anger that bubbled within young Stephen at that point. The youngster felt that his father had taken away from him his only chance at furthering his cricket dream. The then young Stephen complained and begged, but his father was unmoved.

"That chance will come again. So, that will wait,” the older Cook told Stephen at the time. “First, you finish this and see how things will pan out."

Years later, two years after retirement, Stephen is grateful that his father stood his ground. After matric, Stephen ended up going to university where he first studied for his BCom degree, and then did his law degree afterwards. A degree that he juggled with playing cricket - he had a lot of late nights of study while on the road with the team.

“I studied for my law degree with University of Joburg, which is theoretically a contact university,” Stephen laughs,” but, if I am truthful, it was very distance learning.”

The experience taught him discipline, hard work and perseverance.

Anyway, the other reason why his dream to play for the Proteas was a bit naïve is that it’s never easy being a second generation athlete. Yes, his father could have given him a head start with teaching him technique and skill early on, and maybe using the family name to open some doors. But, bearing the Cook name also meant that Stephen was always going to be judged against his father’s abilities and success. It was always a cloud that hovered over him. The moment people realized that he was Jimmy Cook’s son, expectations went through the roof.

“It was very hard to escape that my dad was who he was. I was constantly reminded of it,” says Stephen. “I think it also hindered me in many ways. If you didn't meet that high expectation, they just said, ‘Well, he's not as good as his dad, so...’ It didn't always help.”

A lot of times, people did not want to see what Stephen could do, they wanted to see what Cook junior could do. It is a lot of pressure. Unbearable pressure for Stephen, who at one point remarked, "I wish someone would write an article where they wouldn't say, 'Stephen Cook, the son of Jimmy Cook.' I wish one day they would say, 'Jimmy Cook, the father of Stephen.' If I can have that once, just for once in my life that way around, that will be amazing."

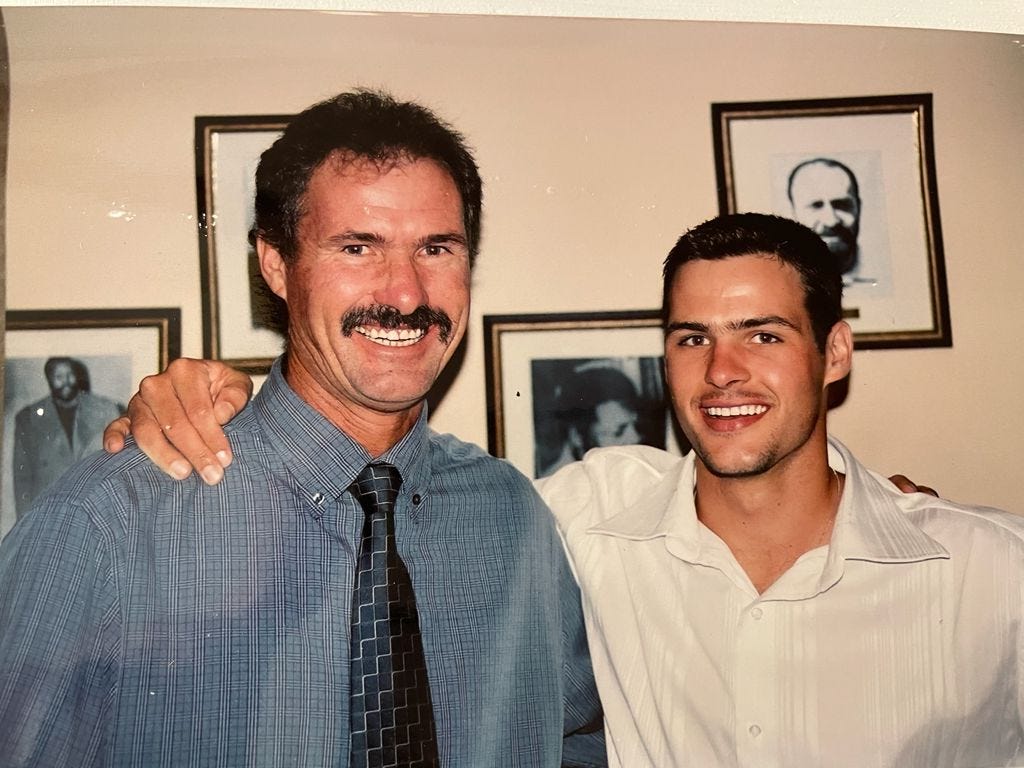

The pressure wasn’t just on Stephen, it was also on Jimmy Cook himself. There’s that season, in 2007, when Jimmy Cook took up a job as an assistant coach with Gauteng Lions. Stephen’s initial reaction was joy. He had always worked on his batting with his father, and now to have him in the team would mean that Stephen would be working closely with someone who understood his game more than himself. It was a singular opportunity.

"I thought it was going to be really good,” says Stephen. “I mean, I had always worked with him, always doing a lot of one-on-one, privately. So now, I was like, ‘I can wrap it all in one. He watches me train all the time, and now he will also watch me in games. That feedback loop will be a lot easier.’"

Things didn’t happen like that. Jimmy Cook tried so hard to not look like he was favoring his son that he almost neglected to give him attention, and Stephen’s career took a few steps backwards.

“I think my dad was so scared of any potential nepotism or situation of favoring his son, that I just didn't get picked,” Stephen shares.

After Jimmy Cook left the Lions, things went back to normal. Stephen went back to working with team coaches at Lions while he worked with his father back home. It was a situation that created what Stephen views as the second phase of his career. In 2009 he broke the First Class record, batting for 13 hours and 58 minutes to put up a score of 390. He surpassed his father’s highest score of 313.

Jimmy Cook moved more into the background of Stephen’s career. Father and son continued to work together, one-on-one, right to the end of his professional cricket career. Who knows, maybe they still do so even after Stephen’s retirement.

Maybe it was a lost opportunity for both father and son, but, instead of feeling hard done, Stephen Cook is philosophical about things.

“That's the beauty of it, the beauty of life, you don't know how things will turn out,” he smiles. “Sometimes coaches whom you think you are not going to gel with because of things that you have heard about them, turn out to be the ones who have a positive impact on your career and development. It’s like good advice, you never know where it's going to come from.”

To support this idea, Stephen recounts how he got one of the best pieces pieces of advice on batting from Mark Boucher. Only that Mark Boucher was not talking to him directly at the time, it was just happened that Stephen was in the same dressing-room as him and he paid attention to what Mark was saying to someone else.

“I remember walking into a dressing-room, mid to early my career, it was a one-day game, we had played against the Warriors,” he says. “Mark Boucher had played for the Warriors and was in our dressing-room visiting for a bit. And I just sat there and I listened to how he was talking and I was like, ‘That's such a good perspective.’ It was probably what I needed to hear at that point in my career. Not that he was talking to me at all.”

Fleeting moments.

Of course, not all of the best pieces of advice that Stephen received were from eavesdropping dressing-room conversations. Some of them were from the senior players he played with at Lions. It is also probably the fact that he has always been surrounded by senior players that he is philosophical in nature.

Without a doubt, it is this philosophical outlook that helped him to develop character and forge his own path and manage to emerge from the large shadow cast by his father’s legacy as his own man.

“The negative moments forced me to think about how I was playing, what I was doing, what were my priorities,” he confesses. “I am always one to think that hardships happen but they can be a real positive.”

And he had a lot of those. From not being selected for teams because he was a small kid who couldn’t hit fours and sixes, to being left out of provincial teams and then to missing out on limited overs cricket because he was pigeonholed as a red ball cricketer, which created gaps in his career.

“Those sort of experiences really built me up,” says the ever philosophical Stephen Cook. “They taught me to deal with adversity, deal with failure, deal with the critics out there - I mean, you're going to be criticized.”

The other thing that they taught him is gratitude, and with that, he doesn’t take any opportunity for granted. For instance, would he have liked to have played more Tests for South Africa? Yes, he would have loved that. But, he is also aware that that would mean that things would probably have turned out differently in the present.

“The path wouldn't be the path. I wouldn't be who I am today,” he says. “And so, I am perfectly content in it. All of this is part of my story.”

And what a story it is that he has. If it is a story that is told in reverse, it would start in 2016, on the night that he received the call from the then SA convenor of selectors, Linda Zondi, telling him to pack up and be ready to join the Proteas squad. It would start with the day he finally realized his lifelong dream to play for South Africa. The call was followed by the longest 45 minutes that Stephen had ever endured. In that period, he couldn’t tell anyone of the news, and his wife, whom he could trust with keeping the secret, was not answering her phone.

Or, if you have a flair for the dramatic, it is a story that would start with James Anderson bowling a leg-side half volley that Stephen Cook clipped off his pads for four, as he began his journey to a century on debut.

“I really soaked it all in that day,” Stephen smiles wistfully. “Everything from singing the anthem to walking out to bat. I thought to myself, ‘There is a chance this will be my only Test. If it doesn't come off here, this is the last Test of the series, you don't know what they're going to do in the next series. It could be a one-off. So I am going to enjoy every moment of it.’ And I really did, I just embraced every moment of it.”

Thank you to everyone who has shown their appreciation of my work and this newsletter. I am entirely freelance and have no intention of putting content behind a paywall. However, for me to be able to continue producing more content, I depend on your patronage. So, please do support my work on Patreon.

Alternatively you could Buy A Coffee.

Also, please encourage anyone whom you think may be interested in my work to subscribe.